'WATTSTAX' AT FIFTY: SOUL'D OUT!

A new boxed set beautifully augments an historic film

On August 11, 1965 two Los Angeles police patrolmen made a violent arrest of a mother and son in the predominantly black Watts section of the city. The officers were white. The prisoners black. As the confrontation unfolded residents of the neighborhood began to gather. A bottle was thrown. The police presence escalated. That night, disk jockey the Magnificent Montague went on the local soul station and used the slang “Burn, baby, burn!” to describe a hot record. Soon it became a chant in the streets as stores, cars, and apartments were swept up in a raw explosion of rage against years of brutal treatment by the LAPD and the LA county sheriff’s department.

This incident ignited six days civil unrest, thirty-four deaths, $40 million in property damage, and the deployment of 14,000 national guardsmen. The Watts riot was the first of the big urban uprisings that occurred throughout the United States in the mid-60s into the early ‘70s, which expressed black anger at institutional racism, encouraged white flight from urban centers, and left scars, both mental and on real estate values in the area, that lingered for decades.

Many official reports were issued. Much hand ringing was done. Many fingers were pointed. But the fundamental damage to the L.A. black community and the aggressive policing of the LAPD was never addressed. (The 1992 riots could be traced to the same root causes.)

In the riot’s wake a group of local activists tried to bring a more positive light on Watts by starting an annual cultural festival. Seven years later organizers reached out to Memphis based Stax records to book their bigger acts to perform. Stax, founded in 1957, by a white brother and sister, had by 1972 been taken over by the imposing Al Bell, a former promotion man and record producer, who was greatly influenced by the ideas of black nationalism and the need for black peoples to control of their cultural products.

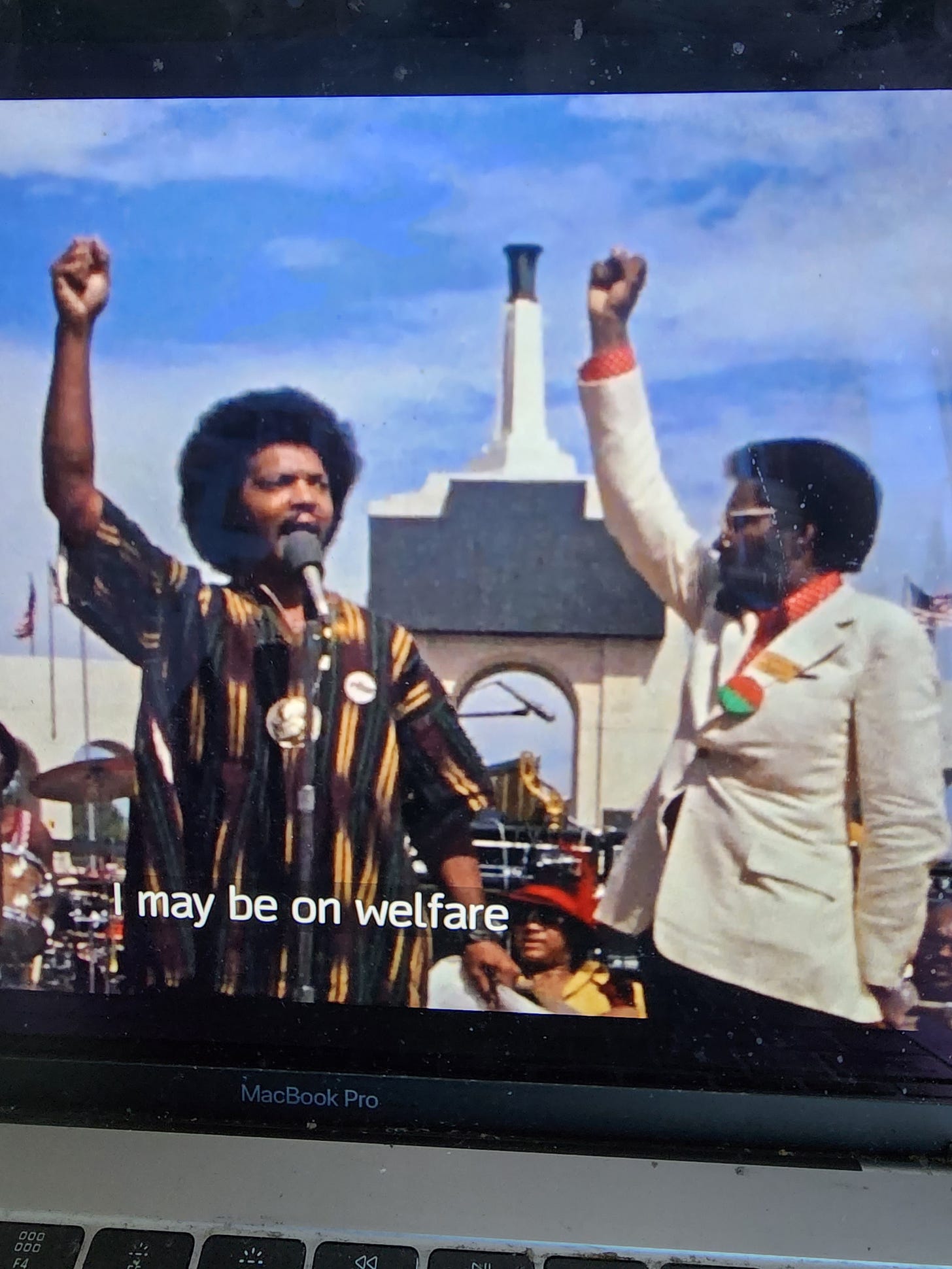

(Reverend Jesse Jackson and Stax Records president Al Bell.)

Moreover, Bell was aware that L.A. was becoming the new home of African American music with Motown having just relocated there from Detroit, the launch of the first black syndicated music show ‘Soul Train,’ and the rise of Hollywood financed blaxploitation movies. To support the Watts’ community, and provide greater exposure for his label, Bell backed the idea for a concert, film and album titled ‘Wattstax.’ The concert was held August 20, 1972 at the L.A. Coliseum. People were only charged $1 for entry, ensuring that entire families would attend. Attendance was estimated at over 110,000, which Bell and company claimed was the second largest crowd for a black event behind only the 1963 March on Washington.

Though the concert was held in summer 1972, it’s the release of the film in February 1973 that is being celebrated with a 50th anniversary vinyl album on Craft Recordings (Soul’d Out: The Complete Wattstax Collection, which comprises twelve discs plus liner notes and photos) and the release of the film on HBO Max.

What elevates the film and the boxed set is that the project is not just a concert film, but is packed with interviews with black Angelenos, show introductions by Rev. Jesse Jackson and filmmaker Melvin Van Peebles (who helped run the backstage area), and hilariously wise commentary from then Stax records signee Richard Pryor. There are few funnier, more authentic, and sharply observed windows into the souls of black folks circa early ‘70s than ‘Wattstax.’ Though directed by white filmmaker Mel Stuart (best known for directing the original ‘Willie Wonka’), he enlisted a team of black camera people whose intimacy with their subjects elicits streetcorner wisdom from brothers sharing a bottle and siters doing hair.

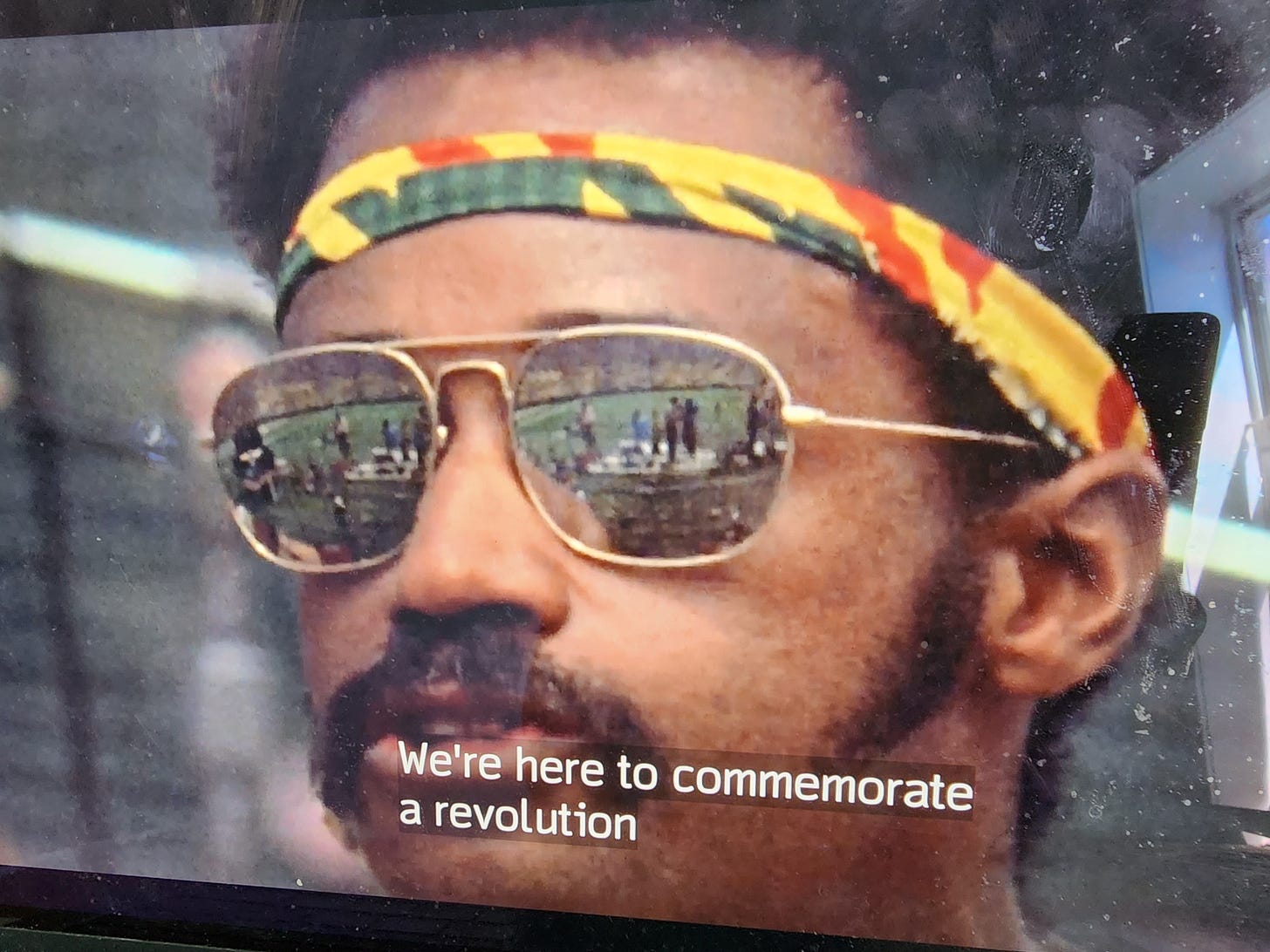

(Melvin( Van Peebles introducing the Staples Singers.)

In addition to the footage shot at the Coliseum, several performances were photographed at other LA locations. The female vocal group the Emotions performed one song at a church. Little Milton plays the blues by a burning fire next to railroad tracks. The hitmaking Johnny Taylor rocks the Summit Club before a crowd filled with pimped out customers. In fact, in the boxed set, the Summit features a slew of previous unheard performances by acts small (Sons of the Slum, Mel & Tim) and the large (the Emotions in full soul mode.)

With the release of so much new music, the film now serves as more of an appetizer for the entire ‘Wattstax’ experience. My favorite moments from the film include Rev. Jackson’s leading the huge crowd through his famous “I Am Somebody” incantation, the blazing hot funk of the Bar-Kay’s “Son of Shaft,” the effervescent Rufus Thomas controlling the crowd with his outfits and wit, Isaac Hayes’ gold chain coat, and every time Richard Pryor and the people of Watts fill the screen.

Stax Records would go bankrupt in a few years, due too much expansion and some questionable bookkeeping. But this film and boxed set are testaments to the epic swept for company’s ambitions and accomplishments. Fifty years later and Stax’s legacy still endures.