Mentorship is a word that’s become a contemporary replacement for apprenticeship. Back in the era where we focused on learning a trade or practical skill, you apprenticed with a veteran in that profession until you reached some level of mastery. In Asian martial arts (or at least the version sold to me in kung fu movies) the “sensei” put his students through years of rigorous training and an upward evolution denoted by various colored belts. But the journey isn’t as clear cut in other advocations.

Coming up in the New York media world of the ‘70s there were internships where, for a limited time – a summer or a semester – where you would be an unpaid worker offered a glimpse of the professional landscape and a chance to impress supervisors with your ambition and potential. In process you might acquire a mentor who’d give advice and make sure you got some opportunities (if you didn’t ask too many questions.)

I had a number of mentors during my college and post-college years – women and men who saw something in me worth giving me a free lunch, letting me watch them at work or read my early journalistic efforts. But no one had more of an impact on me than Robert ‘Rocky’ Ford, my mentor, my roommate and my friend, who died May 19, 2020 of natural causes.

Rocky always reminded me of Woody Allen circa ‘Annie Hall’ (a film we actually saw together at an East Side cinema). Meaning he was constantly quipping, super observant New Yorker with a dry delivery of sarcasm and wit. If he hadn’t fallen so hard for music, I’d always imagined Rocky as a stand-up comedian, drolly saying one liners on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show. Instead, he employed his humor as a default protection against disappointment, pressure, and life’s limitations.

Rocky’s mother and father had been part of the unheralded urban migrations of working- and middle-class black families from Brooklyn and Harlem to New Jersey, Queens and Long Island that occurred in the ‘50s and ‘60s, bringing the families of people Eddie Murphy and others to the suburbs. In the case of the Ford’s Robert Sr, a cook turned corrections officer, and his wife Addie took their three kids from a six floor walk up on Amsterdam Avenue and 152nd Street in Harlem to 205th Street and 115th Avenue in St. Albans, Queens which, along with Hollis, Cambria Heights, and Jamaica, would be a middle-class heaven for scores of African-American households.

Rocky was the most important male figure in my life from age 20 to 25 and, on a day-to-day basis, had more effect on my overall development than my father. I imitated his jokes. I used his techniques to pick up women (he had many.) I learned to review music following his tutelage. He got me an internship at Billboard and, after I graduated college, ended up working there from 1982 to ‘89. So basically Rocky gave me the foundation for my career, a debt that can never be repaid.

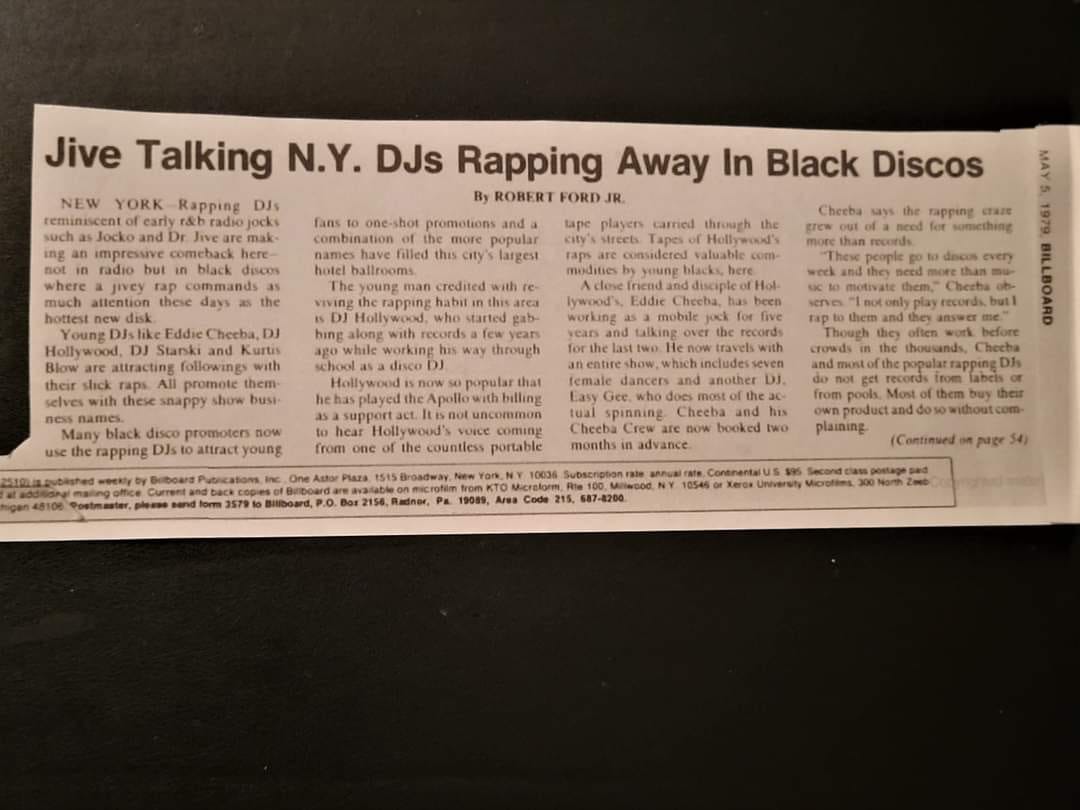

Rocky, was a key figure in the growth of what we now call hip-hop. In May 1979 he wrote the first trade publication article of rappin’ DJ’s for Billboard. His curiousity led Rocky, along with his partner J. B. Moore, to produce the Kurtis Blow hits, “Christmas Rappin’” and “The Breaks,” the first gold rap singles on a major label, as well as “Rappin’ Rodney” for Rodney Dangerfield. The duo would also produce Full Force’s first three albums, while Rocky would work with the vocal group Hi-Five, who had a 1991 hit with “I Like the Way.”

Rocky’s May 1979 piece in Billboard was not only the first on rappin’ DJs in a national magazine, but led him to co-produce Kurtis Blow’s “Christmas Rappin’.”

Because of Covid-19 restrictions there were few funerals in New York City in the spring of 2021. But his wife Linda was able to arrange a small one at a Brooklyn mortuary. The ceremony was limited to immediate family, but she was able to invite me to a pre-funeral wake. His son had grown up to be a play by play broadcaster for the Houston Astros, making him one of the few African-Americans to have that job in all of major league baseball. I saw a few relatives of Rocky I knew from back in the day and a couple of ‘80s acquaintances.

But mostly I sat in a pew and looked at Rocky in the casket, remembring his vitality and humor. Linda had a soundtrack of some of Rocky’s favorite songs and screens that flashed photos of his life. I was in one photo, which made me happy. I was a part of his seventy-year journey. It felt good to be in the company all those he’d touched.

At some point I got up to get some air outside. I felt choked up, like my words were stuck in my throat. Outside I stood next to the front door, breathing deeply. Then I found myself walking across the street and I just kept on going. Before I knew it I was ten blocks away. I kept on walking, going through five neighborhoods and countless blocks, not really in my body, just putting one foot in front of the other until I was standing in front of my home with the booklet from Rocky’s wake clutched in my hand.