Remembering Jack the Rapper

The DJ, newsletter and convention origanizer was a real OG MC

With the coverage of hip hop’s 50th anniversary growing this year, my mind wandered back to what was considering rapping back before the explosion of “Rapper’s Delight” in 1979. People site the Last Poets or Gil Scott-Heron or even Pigmeat Markum. But my mind goes to a colorful character who went by the name Jack the Rapper aka Jack Gibson, who’d been radio DJ, a promotion man for labels, publisher of a newsletter and owner of an annual convention both known as Jack the Rapper.

Jack’s career went back to the earlist days of radio entertainment in the 1930s when he was a actor on radio dramas out of his native Chicago. When live orchestra performances gave way to played records on air Jack became a disk jockey, following in the footsteps of Al Benson, a jive talking DJ at Chicago’s WJJD and is generally considered one of the first black announcers’ to bring street slang to the American airwaves while playing swing and bebop sides. Jack apprenticed under Benson and then developed his own style, labeling himself Jockey Jack and had publicity pictures taken of himself straddling a microphone and turntable in jockey silks.

His own air sign on was: “They call me a jockey, cause I sure know how to ride/ First in the middle and then from side to side/ Ride Jockey Jack! Ride!”

In 1949 Jack moved from Chicago to Atlanta to join WERD, the first black owned radio station in the United States, where he embraced the emerging sound of “jump blues” that eventually became widely known as rhythm & blues. He became the centerpiece of a group of early black DJs, who called themselves “the original 13,” who’d gather every year for drinking, gambling and general debachery. Using street slang, snappy patter and sexual innuendo, these jocks created an air style of rhyme and jokes that was the template the early NYC rapper’s pulled from in the ‘70s and into the early ‘80s. With names like Doctor Hep Cat, Daddy-O, Honey Boy, and Jack the Rapper, these R&B radio announcers are the direct ancestors of the flashy names of people like Hollywood, Love Bug and Kurtis Blow.

Jack would help found NATRA (National Association of Television and Radio Annoucers), an advocacy group for black DJs, and later worked in publicity for the very young Motown Records in the 1963 and then had a similar job with Stax in Memphis from 1969 to ‘72.

But his most enduring legacies was the creation of his newsletter, Jack the Rapper aka “the mellow yellow,” and an annual convention with the same name that he started in Atlanta in June 1977. From a modest start the event became a must attend event for any and everyone in black music until its end in 1994. I attended my first Jack the Rapper in 1981. Walking into the lobby you’d see Billy Eckstine talking with some dapper older cats in one corner, Jerry Butler and Gladys Knight chatting by the bar, and Kurtis Blow and his roadies checking into the hotel. Generations of music history rubbing shoulders. One of the great nights of my life was sitting with a few industry friends in a restaurant with windows that looked out at the lobby, taking in the fun frenzy of the scene at Jack the Rapper.

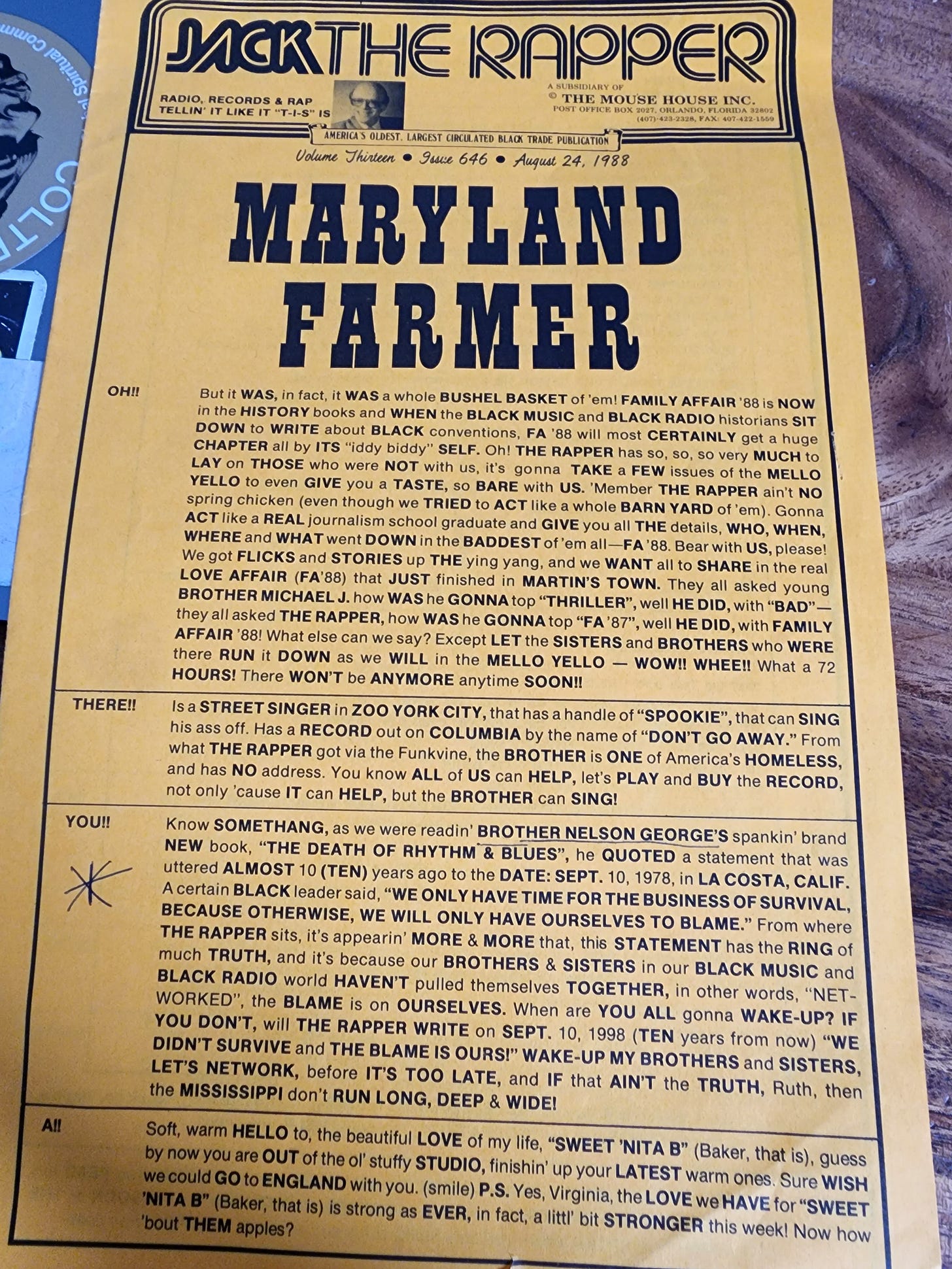

Below is a copy of his newsletter from 1988, which was always published in an oversized format on yellow paper. When you read the words in CAPS, think of them as said in a loud, MC voice. I keep this copy because there is a reference to my book The Death of Rhythm & Blues. Jack mentioned it because there’s a section of the book devoted to his career and the colorful history of African-American radio DJs. You can also order on line his own book, Jack the Rapper: The Incredible Life Story, on Amazon.

For those of you wondering why the headline Maryland Farmer, it was old slang for a curse word that contains the words M and F.