JAMES MTUME WAS "A GOOD BROTHER"

The musician, songwriter, producer and broadcaster died two years ago

It’s been two years since James Mtume died. But on his birthday, January 3, I wanted to invoke his spirit and honor his mentorship.

When I was thirteen, I spend the summer in the Model Cities program, a government initiative to calm the ghettos after the ‘60s riots that put kids in schools and paid them a stipend. It was one of those “wasteful” liberal programmed that would be scrapped by Richard Nixon when he launched his “war or drugs.” That summer I earned my money attending a loose set of classes, workshops, and field trips. One class I’ve always remembered was taught by a brown skinned, round Afro wearing brother with a very cool, revolutionary vibe. In one class he made us read three different newspapers about a robbery and compare the headlines and perspective. It was media training from a black male voice that I could respect.

Cut to six or seven years later and I meet James Mtume.

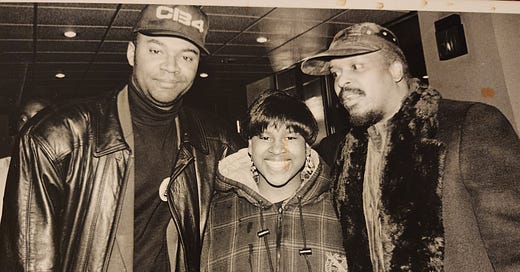

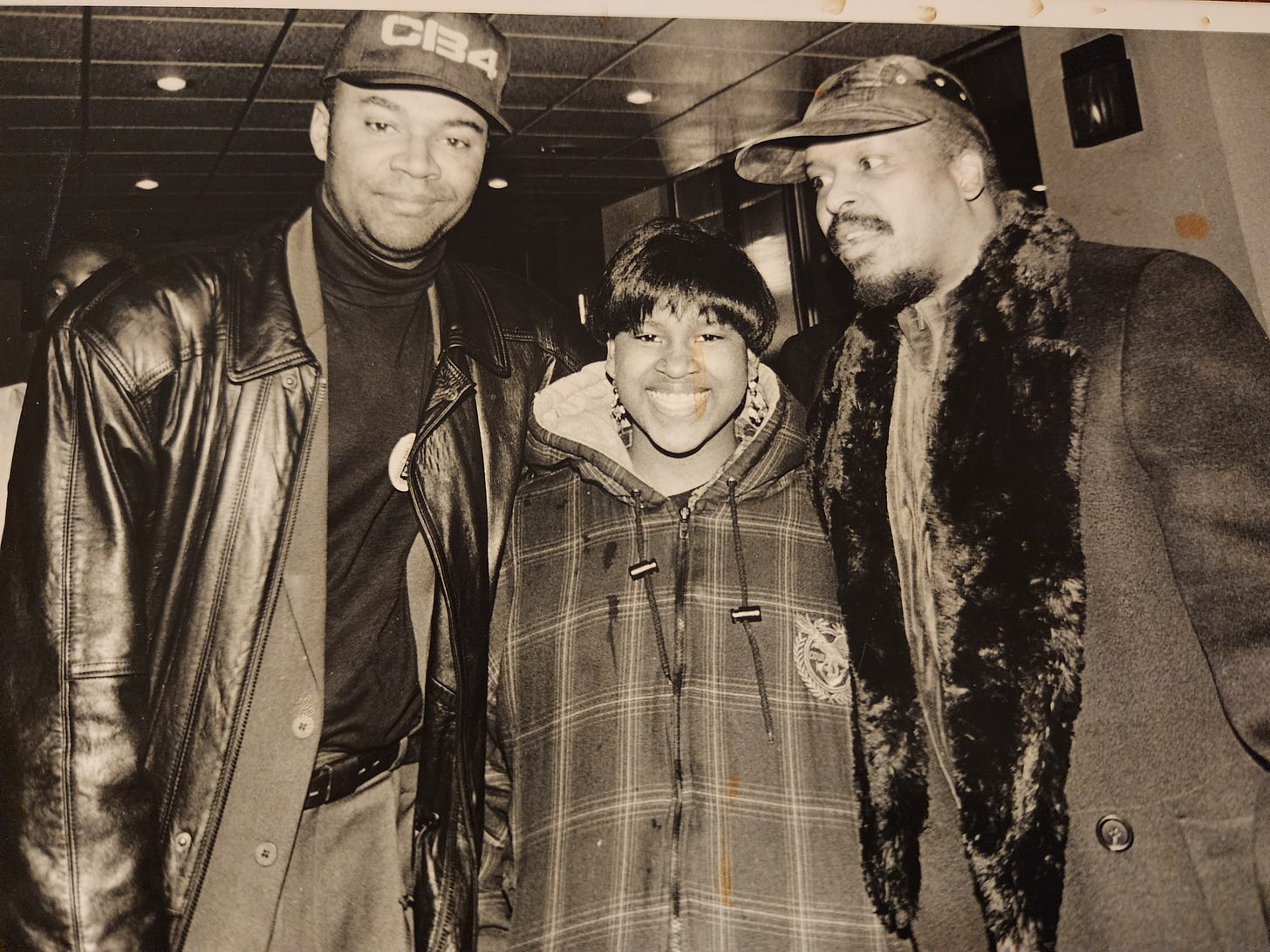

IN 1993 WITH MTUME AND HIS DAUGHTER BENIN AT THE PREMIERE OF ‘CB4’ IN TIMES SQUARE

I don’t actually remember the circumstances, but I’m sure when I was still an intern at Billboard magazine, since when I got my first full-time professional gig my first article was about him. That was in January 1981, so I’d definitely sat down with him in 1980. What I can say, without a doubt, when I was twenty-three Mtume was like that brother from Model Cities – a smart man who always enhanced how I saw the world.

Mtume – songwriter, producer, radio personality, activist – was, like a lot of the men I’d admire, a multi-talented thinker and iconoclast, who had multiple threads to his life story. He grew up with two jazz father’s – his biological was saxophonist Jimmy Heath and his step-father was pianist James Foreman. At the home Foreman shared with Mtume’s mother Bertha, touring jazzmen were regulars for dinner, stopping in for food and conversation before jamming at Philadelphia jazz clubs. Living in that musical environment, Mtume became adept at piano and various percussion instruments.

As a teen Mtume entered the very white world of competitive swimming, eventually winning an athletic scholarship to Pasadena City College in California. While at school he came under the influence of black nationalist philosopher Maulana Ron Karenega (best known today for creating the Kwanzaa holiday) and his US organization. Mtume, which means “messenger” in Swahili, was a name given to him by Karenga, an apt name for a man who would speak with words and music.

After college Mtume moved back to the east coast, relocating to the Newark, New Jersey area where he worked on Ken Gibson’s successful bid to become that city’s first black Mayor in 1970 and became close with poet, playwright and political activist Amiri Baraka, who had his flourishing cultural nationalist group in the city.

Throughout his interest in athletics and cultural nationalism, music remained central to his identity. The debut album was titled, ‘Alkebu-lan: Land of the Blacks’, was recorded live at the East, a black cultural center in Brooklyn and released on the progressive jazz label Strata-East. He played percussion with pianist McCoy Tyner and trumpeter Freddie Hubbard before joining Miles Davis’ latest ensemble in 1971 for a crucial five year stint. During Mtume’s tenure with the Miles, the band leader embraced a hard charging funk style that expanded his audience and was blasted by jazz critics. Miles’ ‘On the Corner’ album was critically reviled, but Mtume saw playing on it was a badge of honor. It didn’t hurt that the bandleader named a composition after him.

During his stint with Miles, Mtume picked up bits of wisdom that he’d would share with the young people he’d mentor. One was the necessity of change, both in your artistic practice and co-workers. Whenever Miles changed his musical direction, he replaced the members of his band or, when he entered his electric period, forcing his players to play new, unfamiliar instruments. In the case of Mtume, Miles had never made Afro-Cuban percussion part of his sound until he embraced funk. (Mtume would make a similar transition in his career in the ‘80s, ditching a traditional analog funk band for a synthesizer driven band. I quit my job at Billboard in ’89 to pursue a career as a novelist and screenwriter, taking a professional leap guided by creative desire as I’d seen Miles and Mtume do.)

Playing with Miles Mtume grew close to guitarist Reggie Lucas and decided to form a highly successful production team that composed a classic duet for Roberta Flack & Donny Hathaway (“The Closer I Get To You”), transitioned Stephanie Mills from Broadway star to R&B hitmaker, and created in the sophisticated soul from Kenny Gamble & Leon Huff. I met Mtume during this phase of his life which, as lucrative as it was, wasn’t his final destination. He saw the writing on the wall for analog and the style of records he’d been making. He broke with Lucas and abandoned analog for a self-titled band based on drum machines, synthesizers and the voice of session singer turned lead vocalist Tawatha Agee. The much sampled “Juicy Fruit” in 1983 is the band’s best-known recording, but “You, Me & He,” a paean to polygamy, reflected the influence of his cultural nationalist days when a man having multiple wives was encouraged.

Along with his commercial success, Mtume’s reputation as a “good brother,” who’d look out for people in need, grew as well. The most extreme example was his relationship with the legendary Sly Stone. By the ‘90s Sly’s innovative, hit-making career had tanked amid drug use and missed shows. He’d fallen into a nomadic state, moving from here to there, wasn’t releasing new music. Mtume got a call from his band member Tyrone Brunson that Sly was looking for a place to stay and had heard “Mtume was someone who helped people.”

So, for several months a man who helped revolution music with an incendiary combination of gospel vocals, pop melodies and funky rhythms, dwelled in Mtume’s New Jersey basement, composing songs while trying to rebuild a life fallen into chaos. But instead of bemoaning Sly’s fate, Mtume saw a lesson in his trajectory. In his view peak Sly - 1967 to 1973 - had made a tremendous, and enduring contribution, to music. A whole generation of musicians had studied his lessons and moved in his shadow. What more did we want from Sly? He’d made a massive mark, changing music, changing fashion, changing how big a black artist could be (at one point he held the record for most sell outs at Madison Square Garden.) Wasn’t that enough?

Mtume’s way of looking at artistic careers shifted my perspective. Instead of deriding some performers as “one hit wonders” or criticizing others for a lack of productivity, Mtume made me appreciate what they’d already done and not judge them for unfulfilled potential. If they’d made a mark in the world – whether it was one record or a powerhouse debut novel – celebrate that accomplishment. See the glass as half-full and drink from it freely. A full creative life will never be filled with hits, but reflections of where an artist is at any given moment in their life. Sly had inspired millions of people around the world early in his career. Whatever he did after that was a bonus. Mtume taught me that was more than enough.

The lessons he learned from Miles and Sly definitely informed Mtume’s the next period in his life. When the hits slowed up, and with hip hop began dominating the charts, Mtume disbanded his group and shifted into composing music for television, produced the music for the Fox series ‘New York Undercover,’ connecting the new jack swing generation of singers with classic soul jams performed at the end of each episode. But his most significant shift was to radio, where on the KISS-FM Sunday Morning show, ‘Weekend Update,’ he was a fixture for two decades years, drawing on his background in activism and nationalism to critique mainstream politicians and new generation leaders. He was particularly critical of charismatic leaders who were heavy on rhetoric and light on analysis.

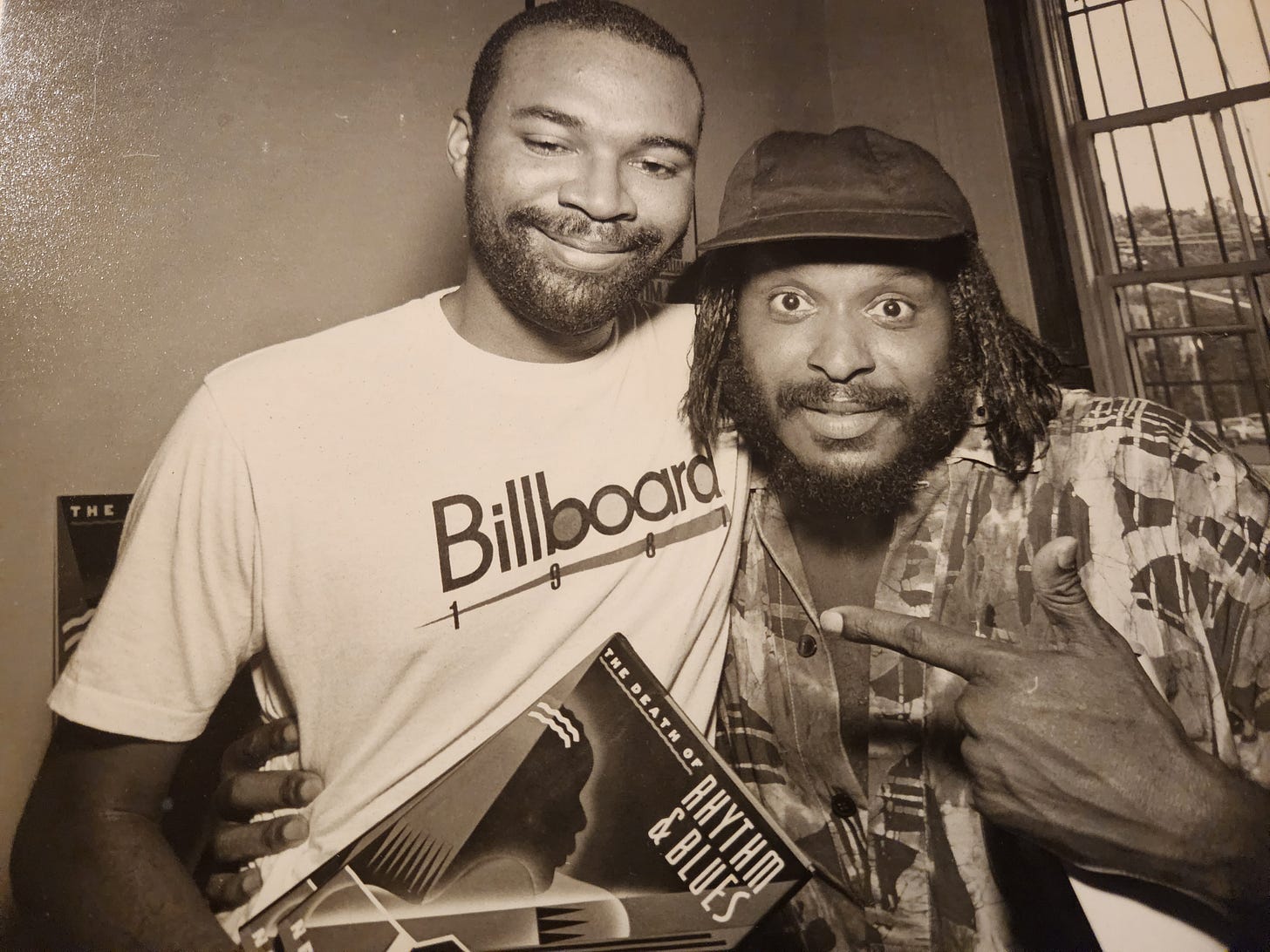

WITH MTUME AT THE BOOK PARTY FOR ‘THE DEATH OF RHYTHM & BLUES’ AT MY FORT GREENE APARTMENT IN 1988

During his evolution from producer to performer to radio host, I was one of the many beneficiaries of Mtume’s advice and wisdom. We talked many times over the years on a variety of topics, through the journey of black music was paramount. The most important insights he offered came in the period of 1987 and ’88 when I was struggling to organize the many ideas I had for a book I was calling ‘The Death of Rhythm & Blues.’ I’d been working on the themes of that book throughout the ‘80s – how corporate control of black music had changed the creative process, how the traditional support systems for that musical culture (clubs, radio, retail) were dying, and much more. I’d call him, Brooklyn to Jersey, tossing concepts around, relating the practical to the theoretical.

One night he suggested I read Harold Cruse’s ‘The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual,’ a biting critique of major figures in 20th century African-American life. How Cruse organized his argument proved crucial in helping me wrangle my material. I wasn’t just a book recommendation but a way of analyzing the world that impacts me to this day. In essence Mtume, like a lot of true mentors, helped me to think more deeply which, in an era of misinformation, has proven been an enduring gift.

In the early 2010s Mtume was diagnosed with cancer. He stepped away from doing radio and focused on treating the disease still did a few interviews. By this time I more focused on filmmaking than writing and shot a couple of epic interviews with him that I hope to cut together some time soon.

The last time we broke bread was at the Meat Packing district Soho House. I was early and found the singers Maxwell and Miguel having lunch, talking career moves, music, and fashion. Mtume joined us and suddenly we had three generations of black pop music at the table. Not sure how familiar Miguel was with the scope of Mtume’s career, but Maxwell was. Mtume held back a bit, not knowing either man well, but it was a cool moment, nonetheless. If either Max or Miguel took anything from the conversation – if it was just one gem – they would have been as lucky to know him as I was.

A little before Christmas 2021 I got message from Mtume’s son Fa that the family was requesting short videos to show his father on his birthday on January 3rd. I send a piece saying how much he’d meant to me and that I looked forward to seeing him again. Fa told me Mtume received messages from friends all over the world and, though his father didn’t usually celebrate his birthday, he did tear up from the outpouring of love. Five days later James Mtume left this realm in his bed, with his music playing, and surrounded by people who loved him.

What an interesting life he lead. Heartfelt tribute🎂❤️on his bday.

was the Tyrone Brunson in Mtume’s band the same person who did ‘the smurf’?