JAMES BROWN & THE BELMAR TRIANGLE

Stumbled upon some unexpected black history in Santa Monica, California

I’ve been coming to Santa Monica, California since the 1980s for dates, dinner and walks on its famous pier. I took it for granted that this coastal town had always been a white middle and upper middle class community. Recently I shot an episode of my Follow the Sound YouTube series there highlighting the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, where the TAMI Show film was shot in 1964. The Rolling Stones, Marvin Gaye, Chuck Berry, Lesley Gore, Gerry and the Pacemakers and the furiously energetic James brown and the Famous Flames made the film, and the location, a pop music landmark.

Brown and company’s performance gave mainstream America its first extended look at the intensity and flair that had been burning up the Chitlin’ Circuit and would confirm Brown’s rep as “the hardest working man in show business.”

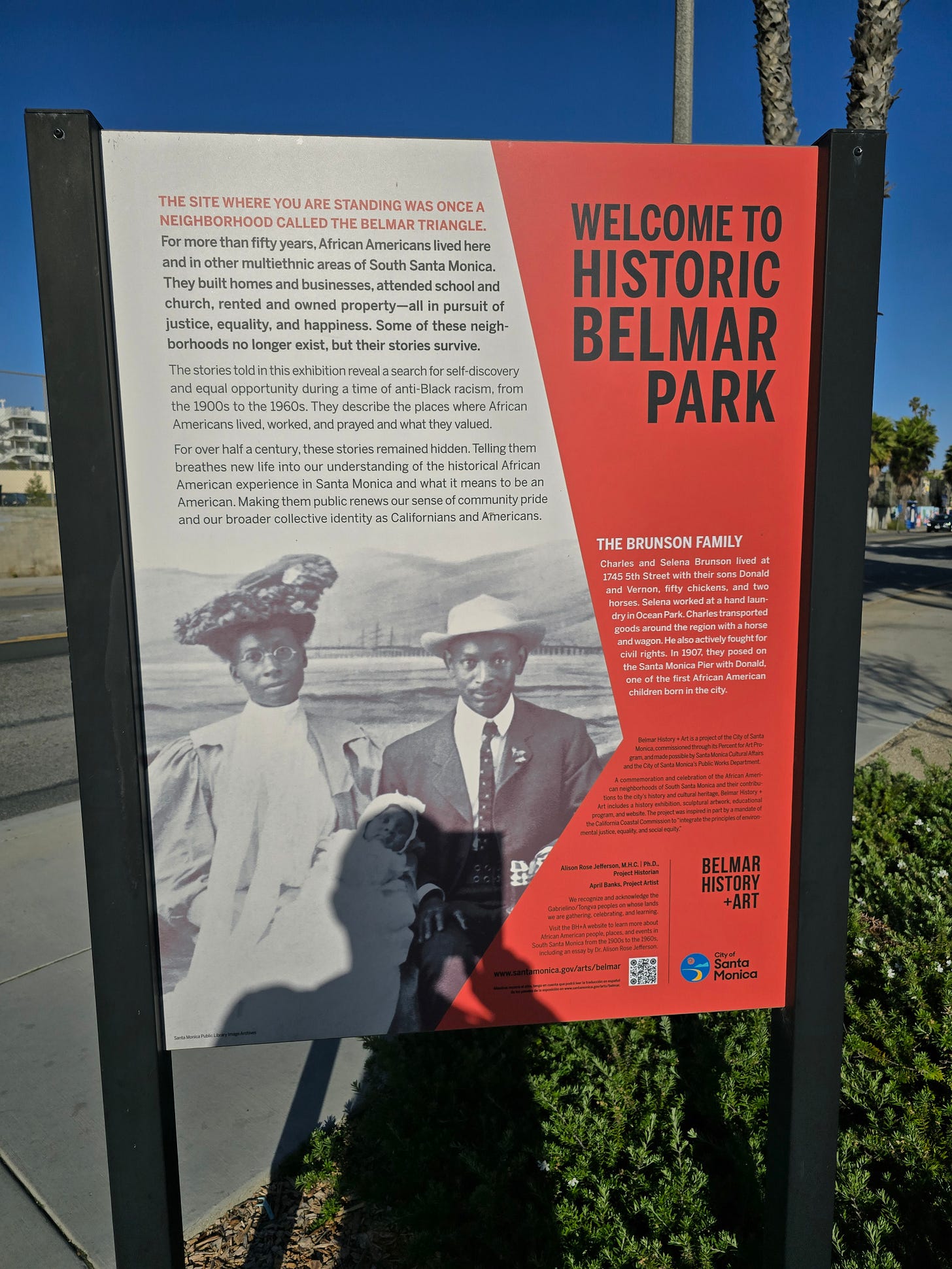

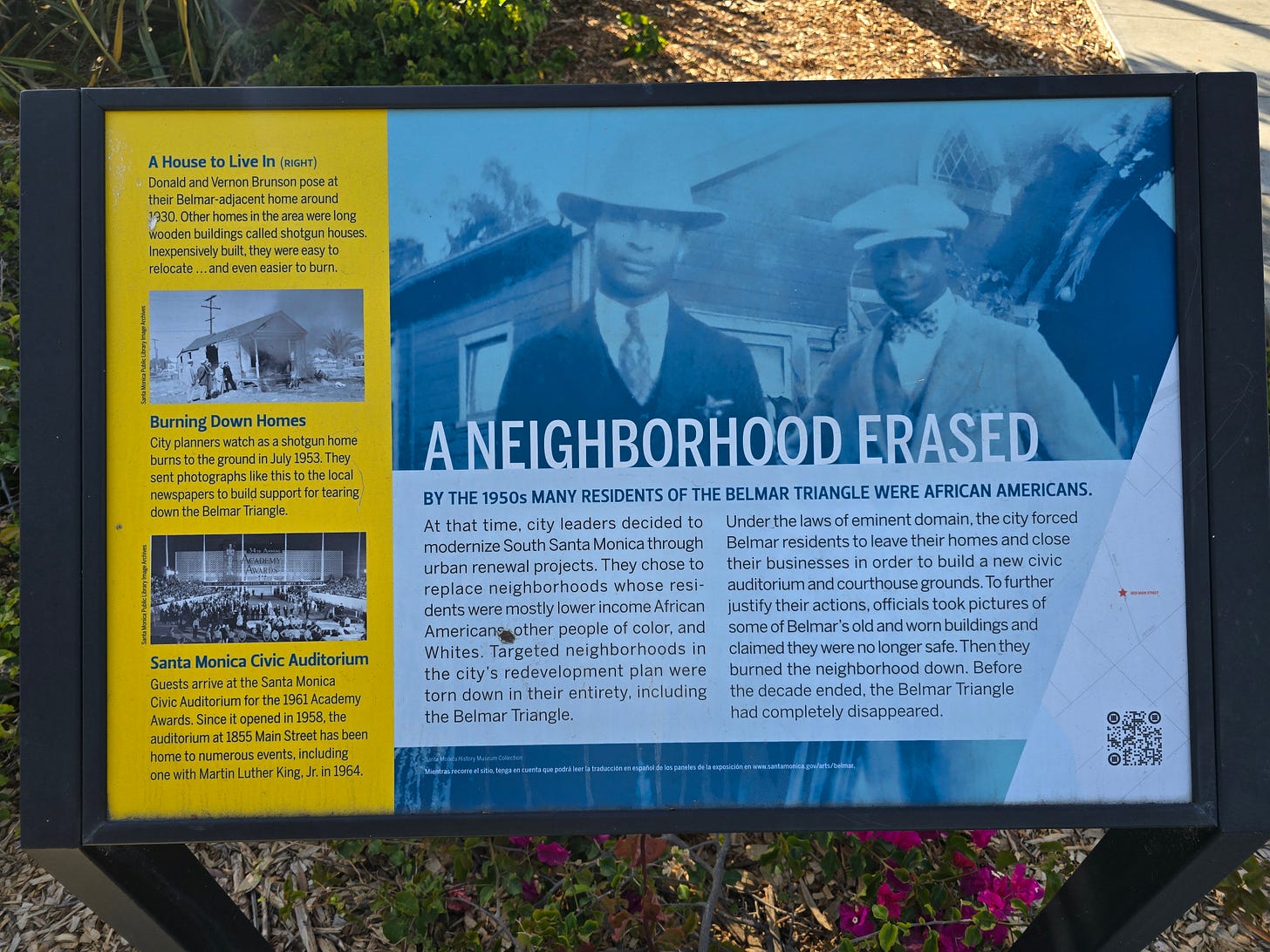

But as I was walking near the Civic Auditorium, I received an unexpected history lesson. Apparently the neighborhood the building sat in, as well as Santa Monica’s surrounding official buildings and soccer fields, had once housed a large black community in the Belmar Triangle, which had literally been burned to the ground in the late ‘50s under the banner of “urban renewal.” Using the power of eminent domain, the city of Santa Monica destroyed Belmar, citing its shot gun shack houses as dangerous, yet not giving its black and poor white residents any compensation or choice in the matter. Reading about how Belmar was removed sounds a lot like how Dodgers Stadium was constructed after the removal of a Mexican community. Whether it was in big cities on the east coast or in Canadian cities like Vancouver, “urban renewal” was a ‘50s and ‘60s code word for removing minority populations from suddenly attractive parcels of land.

Watching the TAMI Show footage becomes more bittersweet feeling, knowing the great artistry of Brown and his peers took place on land were they might have once had friends and might visited for dinner just a few years before. It’s good of Santa Monica to have documented the erasure neighborhood, though I wonder how many of the folks who come to play in Belmar Park have read these signs?