ENCOUNTERS WITH WHITNEY HOUSTON

Remembering the icon the week of her birth

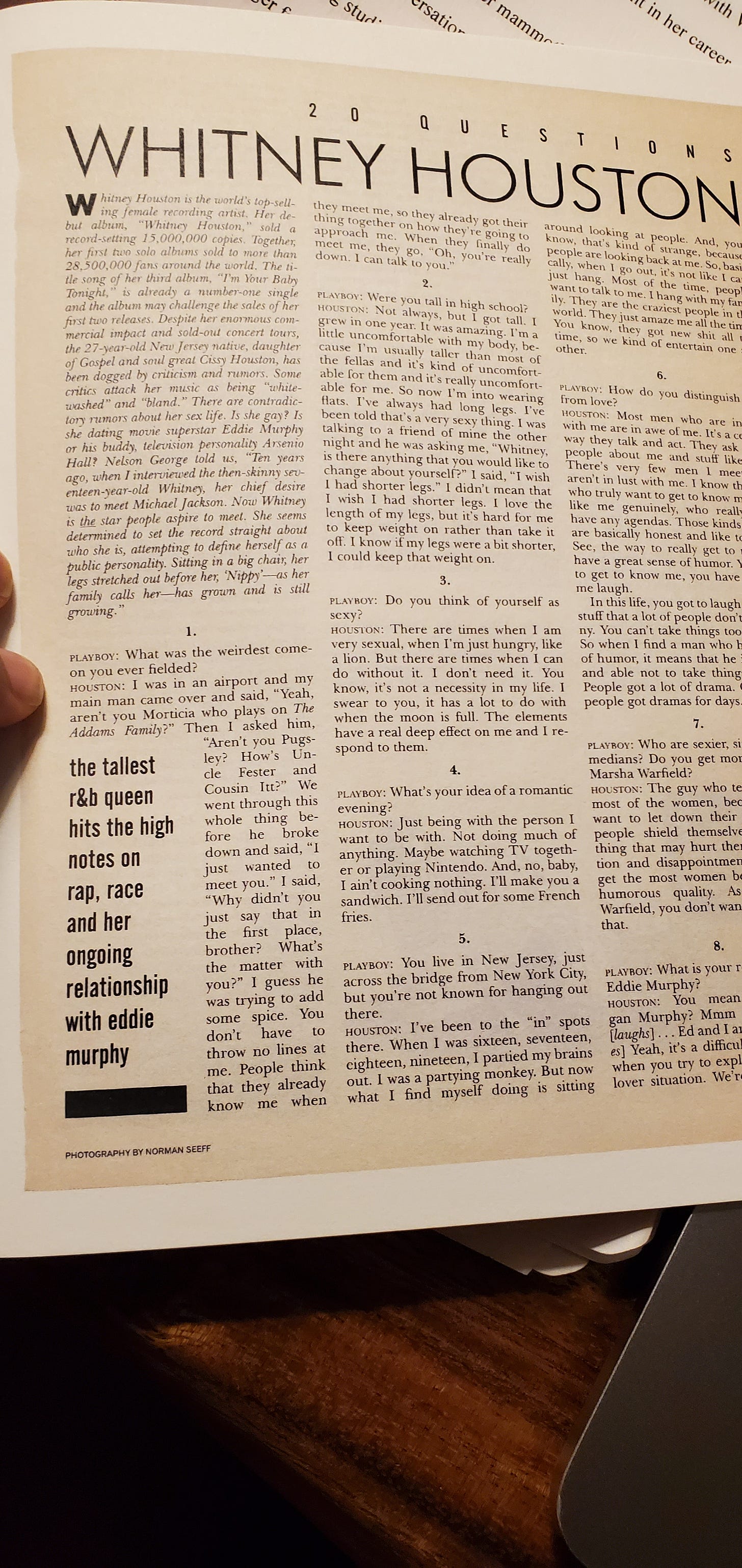

I wrote short record reviews for Playboy magazine throughout the ‘90s, which was a steady check and not very challenging work. But my dream was to conduct one of those epic Playboy interviews. It was an assignment I never landed. My consolation prize was conducting a couple of what they called 20 Questions, which was kind of a mini-Playboy interview. I did one with Chris Rock which, honestly, wasn’t very insightful, since we were good friends and kind of walked through the conversation. However, my 20 Questions with Whitney Houston in 1991 sticks with me, since it turned out it was at a pivot point in her career and life.

My connection to Whitney pre-dates her mammoth-selling 1986 debut album. Her potential stardom was a hot topic of conversation in the clubby world of New York R&B music. In the bars, clubs and recording studios executives, musicians, and tastemakers of the day talked about this gifted teenager from New Jersey usually referred to as “Cissy Houston’s daughter.”

Cissy, while never a solo star, sang lead in a stellar vocal trio, the Sweet Inspirations. She was a respected veteran of the gospel and soul worlds, she’d sung background for both Aretha Franklin and Elvis Presley. Not only was Cissy known as a fine singer, but her cousin was the pop/soul diva Dionne Warwick. So her daughter definitely had a serious pedigree. Moreover this teenager was tall, thin and beautiful and, in fact, had already been making money as a model in New York.

The first time I heard Whitney’s voice was in 1982 when she was 19 years old. She sang a ballad called “Memories” for a New York art-funk band called Material, which was a critics’ darling though they never sold very many records. It’s an odd, arty song that juxtaposed her vocals with the saxophone of avant-garde jazzman Archie Shepp. In the first verse Whitney’s youth is apparent as she seems to walk through the song. But by the second verse there’s a strident sensuality to her voice that belies Whitney’s age. In fact there’s a heaviness, a darkness that kicks in when she sings the lines “you can’t stay but you can not go” that announces very adult emotion. If Whitney’s young voice was a river it would have been clear and seemingly shallow, but below the surface it had thick, inky layers with a current that got stronger with every stroke.

Though I was already at Billboard magazine, I was free-lancing like crazy to pay bills and earn extra money to help my family. As a result I also wrote for the very un-prestigious Black Beat, a pulpy teen appeal magazine I could sell short profiles to for $125 a shot. So I pitched them a piece on the young singer/model and got in contact with her publicist.

We met at an office in the West 50s off Eighth Avenue one gray winter afternoon. She was tall, light, pole-lean, with short, close cut hair and with very little makeup. She wore tight jeans, a sweater, and a very mischievous smile. Despite her slight frame Whitney’s speaking voice had the huskiness of a grown woman with a bit of roughness that said I-am-not-innocent. I’d already heard stories that Whitney partied hard, didn’t back down from a confrontation and was, rumor had it, bisexual.

I remember her manner more than the substance of our conversation. The actual article itself is lost to pulp magazine history. What I do recall vividly was her fascination with the Jackson family. Not just Michael, but all the brothers. She seemed obsessed with the idea of this family of music. After all, she’d come from one too. Being young, black and famous was tremendously appealing to her.

If you see Whitney’s official Arista Records signing photo you’ll see the Whitney that I met. She sits with Arista president Clive Davis and Gerry Griffith, the A&R man who signed her. No weave. No gown. No high heel. The natural “Nippy,” (her family nickname) belied the glamorous looks she’d soon be known for.

The first time I heard her sing live was at Sweetwaters, a popular black music watering hole on Amsterdam Avenue a few blocks up from Lincoln Center. Unlike most young singers Whitney had excellent pitch and didn’t do much show-offy riffing. Instead her tone was clear and she stayed close to the melody, singing through the song and not around. If young Whitney had been a contestant on The Voice, the judges’ chairs would have swung around in unison.

My initial reaction was that as a recording artist Whitney would be a sleeker, more girlish Aretha Franklin with Diana Ross’s crossover good looks. But the ‘80s weren’t the ‘60s. For Davis and Griffith the surest way for a black singer to reach the pop charts in that era was with a melodic mid-tempo song or a big pop ballad, a formula defined by Quincy Jones’ Grammy award-winning ‘The Dude’ (“100 Ways,” “Just Once”) and Lionel Richie’s string of ballad hits with the Commodores and as a solo artist.

Everyone who was anyone in the world of pop music was trying to submit songs for Whitney’s album. One of them was a New York-based producer/singer/songwriter named Kashif, who was at the cutting of edge of black music and technology. Aside from the usual 808 drum machine and electronic keyboards that had become the norm, Kashif employed a Fair Light computer with which he was able to sample voices and sounds in ways more sophisticated and less obvious than what was happening in hip-hop at the time.

Aside from being a hit-maker, Kashif was part of a sparkling crew of talent under the management of Hush Productions, a company run by a slick operator named Charles Huggins. Under his Hush umbrella Huggins handled the career crooner Freddie Jackson, belter Melba Moore (who was Huggins’s wife), producer/writer Paul Laurence Jones and songwriter La Forest ‘La La’ Cope. Aside from his production company Huggins owned a three-story structure on 58th Street just off Broadway that housed his offices as well as a recording studio, making Huggins one of the few black men to control any midtown Manhattan real estate.

Because of Huggins’ stable Hush Productions was a natural place for Arista to look for music to showcase Whitney. Along with La La, Kashif created “You Give Good Love,’ a mid-tempo ballad that opens with glistening keyboards and surrounds Whitney’s warm young voice with a quietly sensual rhythm. The arrangement was calculated to touch on the texture of contemporary R&B, but with a paint-within-the-lines vocal that showcased the beauty of Whitney’s voice, though not its full power.

The first time I saw Whitney, the newly packaged pop diva ,was at the same Bottom Line cabaret where I’d first seen Prince a few years before. “You Give Good Love” was out and rising and I’d heard an advance of the album, which I’d found disappointingly soft and bland. The tomboy I’d met a few years ago was wrapped (or trapped) in easy-to-digest ballads and perky post-disco dance tracks. I particularly disliked “The Greatest Love of All,” which had been a minor hit for George Benson in 1977 and, for me, was a self-satisfied anthem for the kind of self-love sloganeering I loathed.

Arista’s very calculating song selection (with “Greatest Love” the primary example) felt to me like a betrayal of Whitney’s gift. This young woman was the heiress to the great tradition of the church-nurtured, gospel-trained, soul diva. It had always been these voices that drove the R&B-based culture I was raised on. For the great soul divas a song’s melody was a guide, not a road map. After the first two verses (or sometimes earlier) they detonated songs with righteous secular fire.

In the mid-‘80s onward many popular black singers sang between the lines or floated around them. But there was very little phlegm, spit or dangerous curves in the vocals. Part of the change was technological. Vocals became increasingly processed and perfect. The breaths that were typically heard in earlier eras were now removed electronically, so that newer recordings had an artificial precision more soothing than stirring. While the 1980s b-boys were looking for the perfect beat, aspiring singers of the period were literally breathless.

I may have had nostalgia for the sounds of my childhood but Whitney, who knew firsthand the commercial limitations placed upon her soul singing mother and her peers, had become the purveyor of songs designed to satisfy mall shoppers and suburban commuters. It was a strategy to overcome the sound (and racial) barriers that had held back so many, especially since Top 40 radio had become a format where all the rough edges – be it rock, country or soul – were sawed off.

But, while critical of this music, I was very aware of the historical context Whitney existed in. The reality was that for too many black performers of the previous generations, soul/R&B had been a confining box inside which they were restricted to black radio, got paid lower concert fees and got chump change for whatever endorsement deals they received. It was a subject I’d discuss with Gladys Knight, Patti Labelle and others I’d interview during my Billboard years. Sometimes it sounded like their great artistry as singers existed inside a beautiful straightjacket.

Whitney, with an angelic voice and MTV-friendly looks, wanted pop stardom, not a market force restricted slice of it. Moreover Whitney claimed to like “The Greatest Love of All” and all the others power ballads she sang. She didn’t view herself as a creature of Clive Davis’s song selection, but as a collaborator with him in crafting a musical package that would achieve sales that superseded Dionne Warwick, Diana Ross, Donna Summer, Aretha and every previous black pop diva. Her mother played a key role in Whitney’s song selctions as well. As a product of the gospel/soul world, who’d also played the New York cabaret circuit, Cissy knew very well the commercial limitations placed on black singers and the opportunities a wider repetorie opened up. Ultimately Whitney’s path to stardom was not dissimilar to that of her mother’s cousin Dione Warwick, who’s biggest hits came singing Burt Bacharch and Hal David’s clever pop concoctions.

Whitney’s record-setting sales were absolutely a triumph of strategy, since they revealed that by the ‘80s there was, perhaps, an exhaustion with the hard-singing, soul-based singing style, not just amongst the audience, but with the singers themselves. Just as blues had gone out of style with black folks during soul’s ‘60s rise, the production-perfect style of the ‘80s made singers less inspired soloists and more like featured performers in sonically perfect big bands. Eddie Murphy’s caricature of the histrionic soul singer in ‘Coming to America’ captured the tendency to self-parody that had made hard soul singing passé for Whitney’s generation.

The big voices were still out there, on display at churches every Sunday, but the singers that got signed to major labels got tamer as the audiences’ taste shifted. (Mary J. Blige, who debuted in 1991, would be the exception that proved the rule.)

Whitney’s choices signaled a change in popular music. The Aretha Franklins, the Patti LaBelles and Gladys Knights trained in the black church were not getting major label record deals and the big voices that slipped through were singing very different material. When I’d get records in my office at Billboard and give them a listen it felt like the synthetic sounds that defined contemporary production muffled these voices’ incendiary power. It didn’t help, of course, that in the music video-driven industry of the ‘80s, heavy-set or dark-skinned singers were not getting a fair shot. Marginal singers with more telegenic looks became the norm. Whitney didn’t have that problem, since not only did she have a big voice, but a model’s build and bone structure.

But naysayers like me aside, Whitney’s debut album sold the most copies ever by any female singer up to that point, making her part of an explosion of African-American pop stars (Eddie Murphy, Oprah Winfrey, Michael Jordan, Michael Jackson) who’d expand the commercial and cultural reach of black stardom.

While Oprah and Eddie were very accessible figures who did lots of interviews, Arista kept Whitney under wraps during her early rise. She did concerts and appearances at radio and record stores, but very few significant profiles that might taint her carefully cultivated image. In the ‘80s, an era of strong pop personalities (Prince, Bruce Springsteen, Madonna) Whitney was something of an intentionally blank slate.

At some point during the marketing push of Whitney’s debut album I met Robyn Crawford, her friend and long-rumored lover. I seem to remember it was at some press event, whether for Whitney or someone else. Either way Robyn made a strong impression on me. In contrast to Whitney, who seemed a touch high strung, Robyn had a very easy, warm presence, an athletic build and husky voice. We talked basketball since she played on a women’s team out in Jersey. Obviously as a friend and business associate of Whitney it made sense for us both to get along, but I genuinely liked Robyn.

My next major encounter with Whitney came in 1988 when I received an invitation to her 25th birthday party at her Mendham, New Jersey home. I didn’t have a car so MC/businessman Andre Harrell offered to give me a ride as my plus one. At the time Andre was a recently retired rapper (Dr. Jeckyll of Dr. Jeckyll & Mr. Hyde), who’d sold airtime for a local news station and was now launching his own hip-hop label Uptown. On Saturdays I regularly played basketball at Brooklyn’s St. George Health Club with Andre and few other young record business types.

Whitney’s mansion was big and imposing, as befitted a pop princess. Unfortunately commoners such as myself were restricted to the grounds where a series of tents were set up with sound systems and banquet tables of food. Celebrities of all kinds – singers, basketball players, actors, Wall Streeters –strolled around with drinks and plates of food.

There was some buzzing amongst the guests that Eddie Murphy was there. The gossip columns had been filled with talk of various Whitney romances with the comedian/actor high on the list. Looking up from the estate grounds I could see into an upstairs bedroom, where my reporter’s eye caught some movement. Up there, engaged in an animatedly conversation, were a pop prince and princess – Murphy and Whitney. They didn’t linger by the window long, but it was quite thrilling to see the two, even briefly, in a private moment.

A few minutes later Whitney came out of the house to greet her guests and Murphy nowhere in sight. Apparently he’d left and headed back to his place in Alpine, New Jersey (known to his fans as Bubble Hill). Murphy’s absence wasn’t missed when I noticed two highly unlikely figures sitting next to each other on bar stools.

On one stool was Bubbles, Michael Jackson’s pet monkey and designated representative. Sitting to the right of Bubbles, wearing matching red leather pants, jacket and cap, was New Edition bad boy Bobby Brown. When Whitney walked over and stood next to Bubbles I witnessed a weird confluence of mid-80s pop culture and, honestly, I thought the strangest part was Bobby Brown’s presence.

At the time Bobby was just one member of a popular hip-hop/R&B group. While known as a charismatic performer, Bobby’s vocals were as rough as his Roxbury, Boston manner and he wasn’t a star of the magnitude of the other men Whitney had been linked with. A few years earlier I’d traveled from Nashville to Memphis with New Edition for a book project. Within that five-member group Bobby was an outlier. Michael Bivens, Ronnie DeVoe, Ricky Bell were one unit, led by Bivens who agreed on most decisions regarding the group. Lead singer Ralph Tresvant wasn’t a strong personality and more often went along to get along.

But Bobby was very much his own man, a solo star in his own mind and a scrapper ready to physically fight his bandmates when provoked. Bobby had hip-hop edge in an R&B context. If there was a group meeting, for an interview or promotional event, chances were good Bobby would be the last to show up. Though he clearly had onstage charisma (he labeled himself “King of Stage”) Bobby’s attitude and vocal limitations made his future prospects uncertain. So, in 1988, the idea that Bobby was a serious suitor for Whitney seemed crazy.

Bobby would soon exit New Edition and cut a solo album, ‘King of Stage,’ that didn’t perform commercially, fulfilling the doubts of his naysayers. MCA Records gave him a second shot and his next album, Don’t Be Cruel, anchored by new jack swing’s innovative producer/writer Teddy Riley and the carefully crafted concoctions of L.A. Reid & Babyface Edmonds, sold about nine million copies and made Bobby the first truly macho R&B singer in a generation.

Despite the vindication of his success, Bobby was still a troubled young man. I interviewed him in a Manhattan hotel after ‘Don’t Be Cruel’ hit. Bobby’s lips were so extremely chapped and burnt they were literally black. Throughout our conversation Bobby kept rubbing his lips with Vaseline. When I asked him about his lips Bobby said, “It’s because I started smoking cigarettes young.” No one in the history of cigarettes has ever had lips that charred from smoking Newports. I’d seen those same charred black lips on crack heads who used a glass pipe to inhale cooked cocaine. I knew what time it was. No surprise that Bobby would never again attain the sales or artistic success of ‘Don’t Be Cruel.’ But notoriety? Bobby would have a lot of that.

I had several pleasant interactions with Whitney over the next few years, but the most significant came when I received that 20 Questions assignment from Playboy. Because I’d been critical of Whitney’s repertoire in print and in interviews I was told I’d first have to meet with, and be approved by, John Houston, her father and manager, before I could sit down with Whitney.

We met one night at a midtown restaurant where Mr. Houston awaited me wearing tinted shades even though it was after dark. Whitney definitely favored her father who had handsome features and a reddish undertone to his yellow complexion. Mr. Houston was a native of Trenton, New Jersey and had the New York area swagger of scores of men of a certain age I’d come across in bars and barbershops. These were men who’d taken plenty of hard knocks yet maintained their pride no matter what racism or street life threw at them.

If his goal had been to chastise me for criticizing Whitney’s pop balladry, Mr. Houston dispensed with that quickly. Mostly he talked about the many people trying to undermine him and steal his daughter’s loyalty, which included Clive Davis and various big name white managers.

But Mr. Houston’s greatest concern was “that Bobby.” Whitney was in Miami rehearsing for a tour but, in his words, “She’s always on that damn boat with Bobby.” It took me a minute to understand that “that Bobby” was Bobby Brown. It was the first time I’d heard that the two singers were linked romantically. Their relationship wouldn’t go public for several more months, but apparently they were already going strong.

Following that dinner I started asking around about Bobby and Whitney. Within the industry quite a few people knew they were seeing each other. However, it was also noted, that Bobby had gained an impressive reputation as a lover and was not the most faithful of boyfriends.

When I went to meet Whitney for the Playboy piece, Robyn greeted me and, gracious as ever, took me in to meet her friend at a midtown hotel room set up for interviews. This wasn’t the teenager I’d met years ago or even the young woman celebrating her 25th birthday. The fame, the acclaim, and the tabloid scrutiny out the urban edge that had always been there. Sometimes we chatted. Sometimes we sparred.

Because the conversation was for Playboy I led with a series of more playful questions about sex and love and Whitney was more than forthcoming.

“Do you think of yourself as sexy?”

“There are times when I am very sexual,” she said, “when I’m just hungry, like a lion. But there are times when I can do without it. I don’t need it. You know, it’s not a necessity in my life. I swear to you, it has a lot to do with when the moon is full. The elements have a real deep effect on me and I respond to them.”

“What’s your idea of a romantic evening?”

“Just being with the person I want to be with. Not doing much of anything. Maybe watching TV together or playing Nintendo. And, no, baby I ain’t cooking nothing. I’ll make you a sandwich. I’ll send out for some French fries.”

Later in the interview we reflected on her teen years and she admitted that the hard-partying rumors I’d were true. “When I was sixteen, seventeen, eighteen, nineteen, I partied my brains out. I was a partying monkey,” Whitney said. But she then added, “But now what I find myself doing is sitting around looking at people. And, you know, that’s kind of strange, because people are looking at me. So, basically, when I go out, it’s not like I can just hang. Most of the time, people want to talk to me. I hang with my family. They are the craziest people in the world. They just amaze me all the time.”

“How,” I asked, “do you distinguish lust from love?”

“Most men who are in lust with me are in awe of me. It’s a certain way they talk and act,” she replied. “They ask other people about me and stuff like that. There’s very few men I meet who aren’t in lust with me. I know the men who truly want to get to know me, who like me genuinely, who really don’t have any agendas. Those kinds of men are basically honest and like to laugh. See, the way to really get to me is to have a great sense of humor. You want to get to know me, you have to make me laugh. In this life, you got to laugh at a lot of stuff that a lot people don’t find funny. You can’t take things too seriously. So when I find a man who has a sense of humor, it means that he is sensitive and able not to take things to heart. People got a lot of drama. Oh, please, people got drama for days.”

Now her father had already told me she was messing with Bobby Brown but, at the urging of the Playboy editors, I asked what was up with her and Eddie Murphy. She smiled and said, “You mean Edward Reagan Murphy? Mmmm…Mmmm.” For the first time in our conversation Whitney’s self-assurance dropped. I believe she actually blushed. “Ed and I are friends.” Then she paused again. “Yeah, it’s a difficult one. It’s funny when you try to explain a friend-and-lover situation. We’re friends and we respect each other. Time will reveal how serious Ed and I are about each other. We enjoy going out together. He likes to talk to me sometimes. It’s not a constant thing. I’ve been talking to him a lot lately. He wants to know how I’m doing. How I’m feeling. How everything is going. It’s that kind of relationship. We’re like friends in love.”

Since we were talking rumors and love I decided to ask about whether she and Robyn Crawford were lovers. Whitney didn’t flinch at that. Guess she expected the question. “What people really see is the closeness between Robyn and me,” she said. “Even when we were kids growing up, people thought we were gay. I think it had a lot to do with Robyn’s being athletic and playing basketball and being very much into fitness. Then she got me into it. That has followed us. People were like ‘Yeah. Yeah. They’re gay. They’re lesbos.’ But I know part of the reason is that most men who say that want to jump into my pants. So they just think, ‘Well she’s gay. She don’t want to be bothered. So she must be gay.’ It’s something that happens to people in my position. I don’t know why. You’re either gay or on drugs. Either your career’s falling down or you’re coming back. I’m tired of it. Now I just take it as a joke, because I don’t make it a point of letting people know or allowing them to know who I’m sleeping with. People automatically want to know that about famous people. Who they doing it to? Who they ain’t doing it to? They want to know all that mess, and for me, that’s private. I don’t think that has to be out on the streets.”

Madonna was kind of the anti-Whitney with her gleefully slutty persona, feminist interviews and embrace of a gay club culture. Whitney, of course, was marketed as the girl next door. It was something Whitney said she felt comfortable with, yet I felt a bit of rebellion underneath her answer. “My mother raised me to be dignified,” she said. “She said ‘You’re going to have to set an example.’ We all know wrong and right. And I’m not here to tell nobody what’s right and what’s wrong. I’m just going to try to be me. I wouldn’t feel comfortable taking off my clothes, because I was taught that that’s really undignified, that it’s really tacky and uncool. And I don’t think that black people can get away with too much. When you’re white, you’re right. It ain’t nothing new.”

In light of her subsequent behavior in the ‘90s this particular answer really sticks with me all these years later. She knew was raised to be a “role model” and was very aware of that pressure.

“At this point in your career, are you confronted with racism?” I asked, genuinely curious about what she’d say. “Racism doesn’t play a part in my life,” Whitney began. “See, the heavy part about racism for me is that it’s just a word we use today. At one time, there was segregation. At one time it was prejudice. And now its just racism. Don’t they all mean the same thing? Doesn’t it mean one group of people discriminating against another group of people? Well, I’ve seen that happen in every country. I try not to take it personally. I will not be discriminated against – not this day and time, anyway. I think about the brothers and sisters who came before me. Talk about racism!”

There was real fire in Whitney’s voice. A general talk about racism suddenly turned personal. “Stories my momma and daddy used to tell me: My mother was the premiere act at hotel in Vegas and she had to set up a trailer outside the back of the hotel because they didn’t want black people staying in the hotel, and she had to walk through the lobby like everybody else. My parents have crossed paths. They did that so that I wouldn’t have to deal with it. So I really have no business siting here talking about racism, because a lot of brothers and sisters have fought the fight so that we can stand here today and be judged not by skin color but by the content of our character.”

Now we moved into that part of the conversation I was most interested in, which was the intersection of music and politics. Hip-hop was ascendant and R&B, both sonically and lyrically, was being transformed by it. The pop crossover strategy of ballads seemed very old fashioned in the wake of Mary J. Blige and other new directions in the music.

“People have criticized you for not being black enough,” I began. “Is that a form of black racism – as if you must conform to someone else’s vision of what black is?”

Whitney did not like this question. Her reply was sharp and to the point. “I wasn’t raised in a household where I was told I had to be this way: ‘You’re black, this is how you have to act.’ I can do whatever I want to do. I think that is an unjustified criticism. I could understand it if I were living white and acting white. What grants you not being black? I help as many black organizations as I can, because I’m concerned about my brothers and sisters. I try to do the best I can in showing that. I don’t know what other way there is.”

“What do you think of Public Enemy’s black nationalist message?”

“I like Public Enemy,” she said. “I like their message. They give young black children a sense of self-esteem. You can be what you want to be. You can be a junkie. You can be a dope dealer too, but that ain’t going to take you nowhere. When rap is a message about something positive that encourages young people of all races – those are the rap records I like most of all.”

“Black nationalism? You know, it’s funny: it seems like everything has turned three hundred sixty degrees… Back in the Sixties, this was what black power was all about. Black nationalism is, like don’t let the white man in. When they have their meetings, we don’t be sitting in on them, so why do they have to sit in on ours? But, again, it’s still segregation.”

My follow-up question was definitely influenced by Chuck D’s criticism of R&B (and R&B radio) but much more polite than a PE lyric. “Don’t you think that rappers are giving more important messages than R&B singers? Isn’t it possible to listen to a million R&B records and not hear anything other than the word love?”

“How can I put this,” she said quite thoughtfully. “Rap has made a place in music young people can relate to, because it allows them to relate to their own situations. People like me, like Michael [Jackson], Luther [Vandross], we have a different approach to our music. Rap artists are dealing with the streets, because they just made it from the streets to the studio. I’ll go back to my old neighborhood and it’s the same shit. It ain’t changed. The crack dealers are still on the corner. I like message music, but I like to deliver a message in a form of love. I understand the street situation, but it’s better for me to do what I can do this way. I like to sing songs that make people happy. And that’s what my songs do. People hear that hook and they’ll be singing it for the rest of their lives. There’s a time for seriousness and a time for being happy.”

Whitney was the child of a gospel-music-singing family, yet went to Catholic schools most of her childhood in New Jersey. I asked her about experience in them and got one of her funniest answers.

“Catholicism is a trip,” she said, which is a great start to any answer. “I was serving a God of love, a God who has compassion and is kind and loves His children unconditionally. Who sent His son here to die for our sins so we wouldn’t be accountable for them. And these people are talking about damnation and purgatory and hell, and if you’re good and you don’t have any abortions and you don’t take any birth control pills, you’re going to heaven.”

“I went to confession one time in the seventh grade. It totally turned me off. I sat behind the curtain and said, ‘Listen, I’m just here because I want to know what this is all about.’ The priest said ‘Well do you have sins to confess?’ I said ‘I do, but God already knows what I’ve done. Why do I have to sit here and talk to you?’ He said, ‘Really you don’t.’ We had a deep conversation within a couple of minutes. He was kicking it and I was kicking it back with him. At the end of the conversation I said, ‘Well, I guess there’s no need for me to be here.’ He said ‘I guess not. Hope that you have found what you wanted to see.’ I said ‘Yes, I did and I won’t be back.” Now I was laughing at Whitney’s combination of confidence in her God and cocky insolence toward the priest. Plus the lady was a damn good storyteller.

We were coming close to the end of my time with Whitney and I wanted to end our talk on a lighter note. So I asked her, “What do singers sit around and talk about?” Whitney waited a beat, said “Non-singers,” and busted out laughing.

“We talk about people who can’t sing. We try to be constructive about it, saying ‘You know if she just did so and so she would be.’ Some we like. Some we don’t. Some we say ‘A pretty good voice if she really works at it.’ Not everybody can sing. I kid you not.”

That was my last time seeing Whitney for several years. It wasn’t until I was working for Chris Rock on his late night HBO talk show in the late ‘90s that I encountered the singer again. In October 1997, we booked Bobby to appear as a musical guest. By then a lot had changed for Whitney and Bobby. They’d married in 1992 and had a daughter, Bobbi Kristina, a year later. Whitney reached a career peak with her performance opposite Kevin Costner in ‘The Bodyguard’ and the massive hit from that soundtrack “I Will Always Love You.”

But, slowly, the couple’s drug use began to overshadow her singing and chip away at her carefully cultivated image. A few weeks before Bobby was to tape our show Whitney recorded a concert in D.C. for broadcast by HBO. Chris and I were given access to an unedited version of the performance by some friends at the network. In many of the close-ups Whitney was drenched in sweat and, too often, her golden voice was raw, even hoarse. Bobby came out at one point and danced an awkward mix of tap dance and hip hop as Whitney sang the Sammy Davis Jr. standard “Mr. Bojangles.” In spots the concert was a real mess. HBO would eventually air a heavily edited version. That taping would foreshadow Bobby’s Chris Rock appearance.

Bobby came on the show to support his fourth solo album, ‘Forever’, which would be his last on MCA Records as his sales had plummeted since the high of ‘Don’t Be Cruel.’ Unlike previous efforts that had top-flight producers like LA & Babyface and Teddy Riley, this album was created primarily by Bobby and a crew of little known collaborators. The single was an undistinguished ditty called “Feelin’ Inside.” Bobby, once a truly dynamic performer, was sloppy on our small stage and by the song’s end he was exhausted, panting and out of breath. Whitney, standing in the wings, looking a bit ragged, not at all like the self-assured woman I’d interviewed for Playboy, rushed out of the wings and comforted Bobby, taking him into her arms as he wobbled on his feet.

Unfortunately there was a technical problem with our tape and Bobby had to perform the song again, which was much less frantic than his original take. Watching those icons of popular music walk away that night was sad as it could be. Neither of them was in the terrible shape we’d see later, but the reality show excesses of the 21st century were dead ahead.

After their divorce in 2007 Bobby slowly pulled himself together, getting remarried and appearing regularly with New Edition, always having space for a selection of his solo hits. But Whitney, of the golden voice and the magazine cover looks, didn’t ever escape her drug addiction. In the process her voice began to deteriorate. Unlike the Aretha Franklins, Gladys Knights and Patti LaBelles, who continued singing strongly into their ‘70s, Whitney’s instrument was shrinking in her forties.

On February 9, 2012 Whitney appeared at a pre-Grammys event with singer Kelly Price in Hollywood. She sang a gospel song, “Jesus Loves Me,” and was a shadow of her past greatness. Two days later she was found dead in a guest room at the Beverly Hilton hotel.

A few weeks after Whitney’s death, I sat on a panel at the Experience Music Conference in New York surveying her career and cultural impact. I told some of these stories. Other writers, like Danyel Smith, who’d interviewed her for Vibe magazine, talked about their encounters with her. A couple of critics who’d never met her, but had theories about her importance, said their piece.

But the day’s most eloquent insight came from Whitney herself. Following her death an audio tape of Whitney’s a cappella vocals singing “How Will I Know” was up loaded to the internet. The panel’s moderator played it and Whitney, sans percolating backing track, flooded into the large ballroom from beyond the grave with the crystalline tone of that made her so very special.

A NOTE TO FREE SUBSCRIBERS: I have almost 700 subscribers to this newsletter, yet only a small percentage of you pay for the content. I love having you read my work, but really need more financial support to keep this newsletter going. A monthly subscription is only $7. Please consider being a financial supporter of #THENELSONGEORGEMIXTAPE.

Absolutely captivating read. You're very fortunate to have interacted with her before her fall.