DISCO, HOUSE AND SPIRIT OF BLACK DANCE MUSIC

A #blackmusicmonth memory inspired by Beyonce and Drake

In summer 1978 I was an intern at the black newspaper the Amsterdam News and was hanging out at the Times Square offices of Billboard magazine where Robert ‘Rocky’ Ford, a member of the production department and sometime writer, was mentoring me on the music business. Among the colorful array of folks working at Billboard at the time was a petite, witty West Indian editor named Radcliff Joe, who smoked a pipe and had very distinctive black & gray goatee. As disco became a force in the industry Radcliff was designated the disco editor, a job that kept him busy, though he didn’t really dig the scene or the music that much.

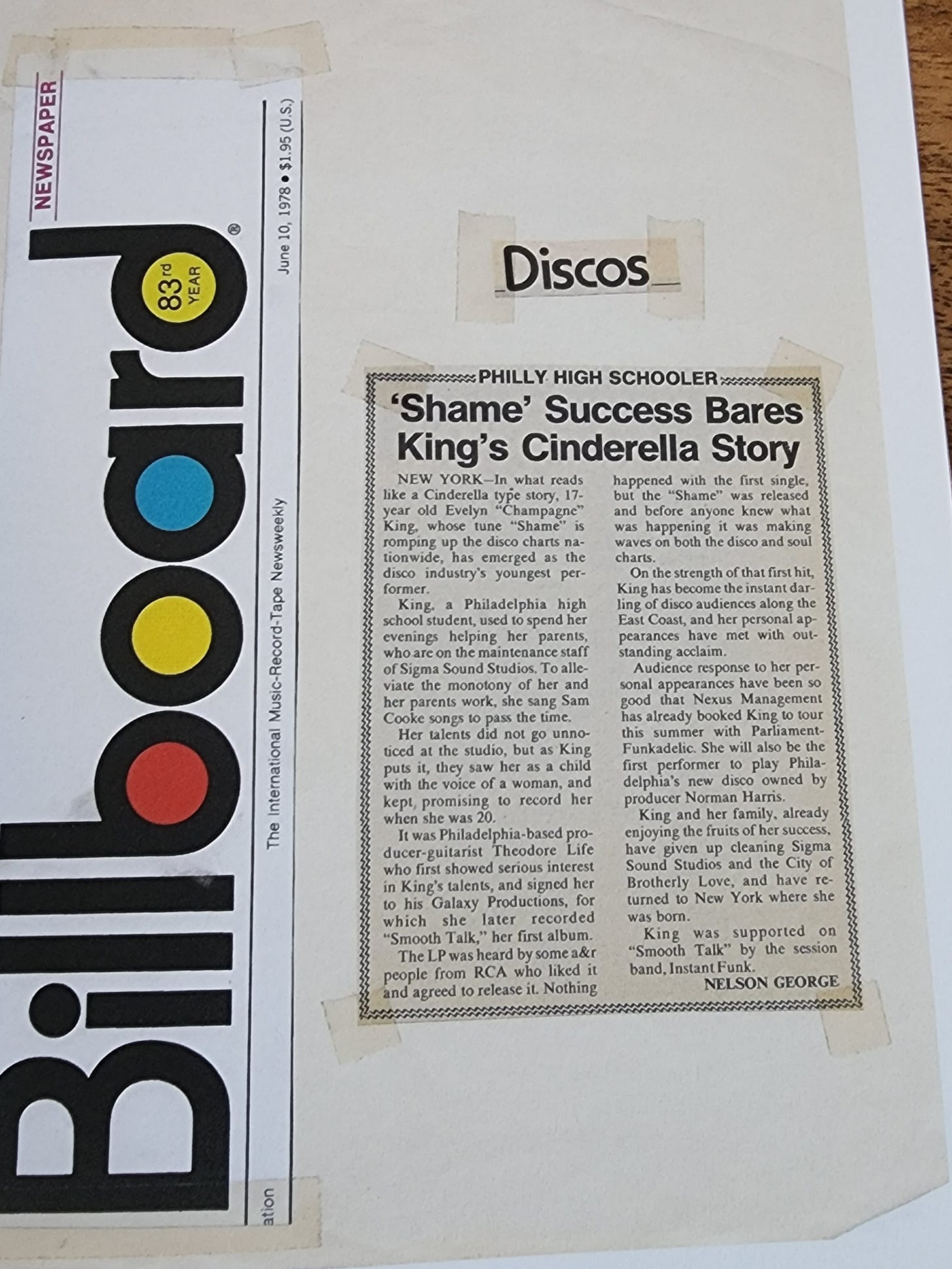

But it was part of Radcliff’s gig (he also covered electronics) and he would eventually pen a book, This Business of Disco, that would be the first on the genre. Since I had some by-lines already in the Am News and was eager for more, Radcliff gave me assignments interviewing emerging disco stars. Evelyn ‘Champagne’ King, just a teenager herself, was my first piece for Billboard and I would interview Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards of Chic soon after. So June of ‘78 was a huge time in my young life. Writing for a national publication, getting on the guest list for industry parties and, for the first time, earning money for writing.

It wasn’t all sweet though. A publicist for Chic peeped that I was very young and called over to Billboard to complain about me. Luckily Rocky intercepted the call and smoothed out the publicist, which allowed me to continue writing for Billboard. So Rocky, who would aid my career and life in some many ways, saved me right at the start. Not only would I continue contributing short pieces and reviews through my college graduation, but would return to Billboard in spring 1982 as black music editor and would work there until ‘89.

It’s worth noting that my entry point into Billboard was the disco section. Though all the artists I would write about were black (King, Chic, Candy Staton), they weren’t getting covered in the regular R&B section, since the line between the disco audience and the black record buying audience was seen as a real one. In truth, at least in the New York area in ‘78, there was serious overlap since local radio stations, WBLS and KTU, played disco also side mainstream R&B. To a great degree artists deemed “disco” were ghettoized by the industry and looked down upon by gate keepers of all races. In ‘78 the “disco sucks” movement was already in full force and would, literally, explode the next summer at a racist, homophrobic event in Chicago.

Almost a year to the day that my piece of King ran in Billboard, President Jimmy Carter would declare June ‘Black Music Month’ at an White House event promoted by the Black Music Association and instigated by producer/songwriter Kenny Gamble and air personality Dyana Williams. The idea is that all genres of music that come out of the black experience in America should be celebrated. So while hip hop has been the dominant form of commercial black music for several decades, post-disco dance music like house, techno, and its many subsets deserve to be respected and celebrated too. It’s funny to me in a summer where Drake and Beyonce have embraced this non-hiphop, non-R&B dance music tradition that’s been so much either disdain or confusion in reaction.

House music was born of the black gay Chicago experience, building upon post-disco musical styles and technology. Over the decade a multi-racial, sexually non-judgemental community has supported house music, particularly the soulful, gospel-meets-drum machine music that evolved out of the original sound. I’ve spend many nights (and days) over the years at house based parties where a wide spectrum of black folks of all ages have sweated together. One of my favorite memories is seeing serious dancers drop baby powder on the floor so that they could glide easier across their corner of the dance floor. Where other forms of black music — looking at you hip hop — are driven by radio and trends in dress or language, house has always been about tribalism and community, existing outside the starmaking machinery of pop, uniting around certain parties, venues and DJs. It’s continued to evolve and influence music globally. South African DJ Black Coffee, who’s produced a couple of tracks on Drake’s ‘Honestly, Nevermind,’ has made some of the my favorite music of the 21st century on his Soulistic Music label, where SA house rules. The Amapiano sound is the lastest cool dance music from South Africa, but its roots are deep in American house.

Pop stars are, by definition, interested in remaining popular. But all the most interesting pop stars are also chameleons, adapting current sounds to update theirs and, perhaps, expand their audiences. That’s the play I see here with Queen B and Drizzy. How do I keep my sound fresh in an ever more fragmented music world? Hopefully their recent releases will take folks back to the roots of house. Its a long way back, a lot of music to hear, dance to and celebrate.

#juneisblackmusic month

The article pictured below is one of the many vintage pieces found in The Nelson George Mixtape Volume 1, published by www.pacificpacific.pub for $28.