When black folks talk about the most important black musicians of all-time, they tend to elevate jazz artists (Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, John Coltrane) or R&B icons (Aretha Franklin, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye) to their personal Mount Rushmore. You can see this tendency on black awards shows, seminars and in museums. One category of black musical excellence that often get ignored is rock & roll. For many generations of black folks’ rock & roll has been seen as “white music” that isn’t relevant to our contemporary existence

.

Chuck Berry, who did as much to revolutionize music globally as any of black music’s many other giants, usually doesn’t get listed alongside the acknowledged African-American greats. That status isn’t helped by the fact that Berry could be stand offish to the point mean to strangers (and to friends) and was arrested on several occasions for a variety sex related offenses. As brilliant as he was as a songwriter and guitarist, Berry was highly problematic on as an individual.

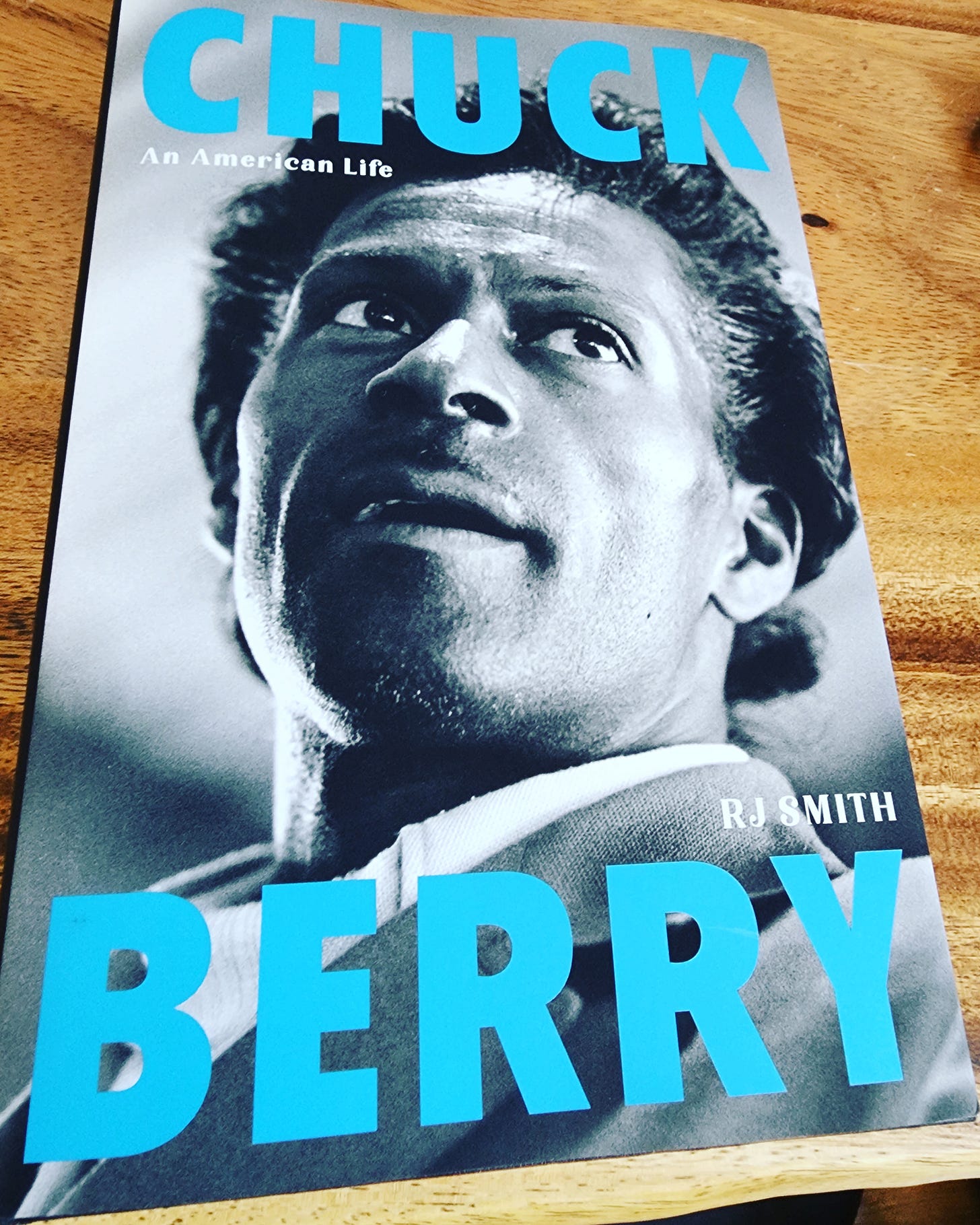

So R.J. Smith’s new biography, Chuck Berry: An American Life, (Hachette Books, 415 pages) will be a challengingly, yet illuminating, read for many for whom much of Berry’s personal behavior was toxic in the extreme. Smith doesn’t shy away from detailing Berry’s arrests and sexual obsessions. He uses court transcripts and contemporary interviews to paint a disturbing picture of Berry.

At the same time Smith details why we should care – Berry’s synthesis of country, blues and boogie woogie, his evocative lyrics, and understanding of the mid-century American psyche mark him as not just a crucial figure in our culture, but perhaps the most influential songwriter of the post-World War II era. For the generation of white musicians who evolved rock & roll into rock there is literally no person more important in defining how that music sounds and what it talked about. How a black man from St. Louis became the bard of white teen angst is the main subject of Smith’s book.

I wish he’d given more thought to how rock & roll came to be “white” and African-American’s relationship to the music. Berry, whose life was marked by constant harassment from police and local authorities in his hometown and on the road, dealt with racism in every phrase of his life and wrote about it, often metaphorically, in his songs. Yet his legacy as a black innovator has faded along with the relevancy of rock & roll. The same way the lack of black interest in baseball has made Willie Mays’ mastery of the game feel remote, so Berry’s potent musicality feels ancient to younger black audiences – if they are aware of him at all.

In our post-literate society few books cut through the noise, Smith’s book is a necessary signpost, a flag in the wind, that brings Berry back into the discussion. He was the original guitar hero and his music still rings bells.