75/85 AND ATLANTA'S AUBURN AVENUE

Where civil rights and social life fell victim to roadway development

In the history of North America urban planning and racism have often had a corrosive effect on African-American culture. in the ‘60s and ‘70s, the phrase “removal of urban blight” was a sentence that justified the bulldozing of neighborhoods from the American South all the way to British Columbia. In working on a number of documentaries in the last decade, its been remarkable how many legendary venues and communities were removed to make way for freeways or, in many cases, left with empty lots for decades. The destruction of many Bronx neighborhoods by the Robert Moses led construction of the Cross Bronx Expressway was well documented in Robert Caro’s masterful book ‘The Power Broker.’ But you can find similar examples all across this continent. Up in Vancouver a vibrant black community known as Hogan’s Corner was bull dozed out of existence for a huge multi-lane freeway under the banner of “urban renewal,” which in most cases meant more roadways to get folks out of the city and into the suburbs.

The role of urban planning in the decline of the once vital “Sweet” Auburn Avenue thoroughfare in Atlanta recently came to my attention on a recent trip South. Lately I have been slightly obsessed with visiting locations crucial to the black music culture I was raised in and Auburn Avenue, with its role in civil rights and social life, was a prime destination. Though rightfully best known for the King Center for Social Justice, Martin Luther King’s birthplace and the Ebenezer Baptist Church, Auburn was home base for a couple of historically important venues and the achievements of several black business people — one celebrated, two others vaguely remembered.

HOME OF WERD RADIO AND SCLC OFFICES ON AUBURN AVENUE

At 320 Auburn Avenue is a building constructed in 1937 that is the long time headquarters of the Dr. King founded Southern Christian Leadership Conference and once housed the studio of America’s first black owned radio station, WERD. It was built by John Wesley Dodds, a black entreprenuer and a Mason. Hence 320 is named the Prince Hall Masonic Temple as a sanctuary from black Mason’s in a segregated city.

In 1949, a group of black businessmen raised the funds to put WERD on the air. White owned stations had been catering to the “Negro market” for several years before this station broke that particular color line. The first DJ on the air at WERD was Jack Gibson aka Jockey Jack aka Jack the Rapper, who’d began his career as an actor in radio dramas in Chicago before transforming into one of the first black celebrity on air personalities. For his Jockey Jack persona who took publicity pix in racing silks and opened his show with this bit of patter: “My momma made a jockey and I sure know how to ride/ First in the middle and then from side to side. Ride Jockey Jack! Ride!” Years later Gibson would be known for his radio trade publication, ‘The Mellow Yellow,’ and his annual Jack the Rapper conference in Atlanta.

While his on air persona was fun loving, Gibson had a very strong political consciousness. When Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. opened the offices of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 320, Gibson would invite the young minister on WERD’s air. According to Gibson he’d drop a microphone out of the window and down to King. When Gibson told me this story some forty years ago, I wasn’t fully convinced it happened quite that way, but after visiting 320 it does seem possible.

(For a fully account of Jack Gibson’s remarkable career and the role of black radio in African-American history check out my 1988 book ‘The Death of Rhythm & Blues.')

SIGN CELEBRATING THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT ANNIVERSARY.

While Dodds is rightly viewed as the Godfather of Sweet Auburn Avenue, many other black business people thrived there. Henry Wynn, owner Supersonic Productions, was very active during the street’s heyday. In an ad the black weekly, the Atlanta Daily World circa late ‘50s, Wynn had activities at five addresses: the Morocco Lounge at 145; Red Top Cabs & Car Wash at 159: the at Treasure Island bar at 176; Henry’s Grill and Cocktail Lounge at 180; and the Royal Peacock Social Club at 186 1/2.

Walking from 320 to any of these Wynn associated addresses on Auburn Avenue requires going under the foreboding Downtown Connector, better known locally as the 75/85, a seven lane elevated roadway that, in 1962, cut Auburn in half after years of construction and a displacement of residents that the avenue recovered from. It wasn’t that Auburn Avenue was the only part of the city impacted by this roadway, but it was particularly devastating to the once tight knit community that went to the area’s black churches (including the Ebenezer Baptist where King and his father preached) and encouraged white flight from the city.

To give national context to the decision to cut Auburn in half, I want to reference to other Southern cities with historic black areas. Overtown in Miami was once the preeminent center for black social life and commerce in that city. It’s where Muhammad Ali trained and where black celebrities stayed at local hotels. The construction of the 1-95 highway began a process of slicing the neighborhood up with freeways, so that during the ‘60s the population went from 50,000 to 10,000. If you want to hear a hint of Overtown’s vitality find a copy of ‘Sam Cooke: Live at the Harlem Square Club 1963,’ one of soul music’s greatest live LPs.

Memphis’ legendary Beale Street wasn’t destroyed to build a freeway, but under the banner of “urban renewal.” Between 1969, the plan the bulldozers arrived, and 1979, Beale Street’s 625 buildings had been reduced to 65. Beale Street had been a stretch forty blocks long. Go there today, after people in town realized they’d destroyed a rich tourist attraction, and you can walk the expanse of “official” Beale Street in twenty minutes or so. What it had been as a hub for black creativity and, yes sin, is lost to memory.

So the split in Atlanta’s Auburn Avenue is part of a history of hostility towards black urban hubs by government’s in charge of urban planning that has fragmented African-Anerican economoc power (black residences and businesses were always the big victims of imminent domain) and disfigured our collective sense of history.

LARGE BUST OF JOHN WESLEY DODDS ON AUBURN AVENUE ACROSS FROM THE 75/85 ROADWAY.

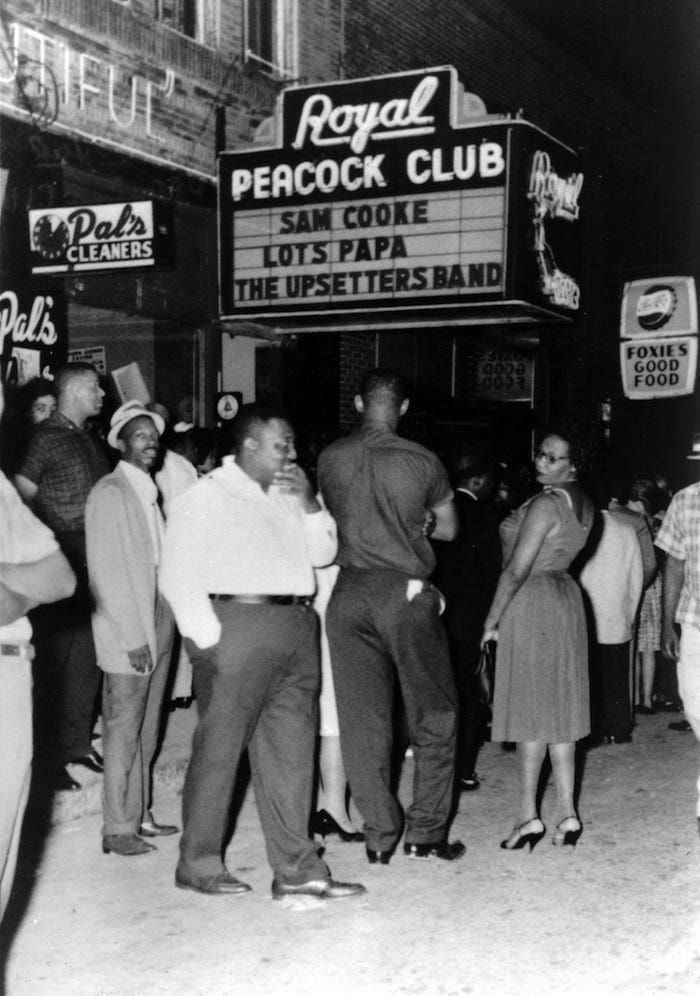

The one structure that‘s remained a live and kicking from the pre-Downtown Connector days until now is 182 1/2 Auburn, which is still known as the Royal Peacock Lounge. It’s billed now as “Atlanta’s original reggae club.” That game was given to it by Carrie Cunningham, who purchased the Top Hat Club in 1949, gave it a new name, redecorated it in a faux Egyptian style and started booking big name black acts. In ‘59 the aforementioned Wynn took over the Peacock and, as one of the bigger black promoters of the era, continued bringing big name entertainers to Auburn Avenue. As the photo below illustrates, in Auburn Avenue’s glory days, the Royal Peacock was a major attraction in Atlanta.

Which makes me look back and ask a few questions.

Would Auburn Avenue (and Beale Street and Overtown) have evolved and survived without the intrusion of urban planners?

Were these areas targeted because they were largely black and, also, attracted whites for food and entertainment when segregationists were fighting integration?

How much was the desire to break these area up a way to limit black political and economic power during the civil rights movement’s very active years?

Who gets to decide what history is celebrated and what’s discarded?

Is any of this relevant now or just an old dude (me) fascinated with how culture is created and disseminated?

These are questions I’ll continue to pursue during black music month in June and in the next year.

OUTSIDE THE ROYAL PEACOCK ON AUBURN AVENUE CIRCA EARLY ‘60S

There’s a great quote about the club from Aretha Franklin, who played there in the years before she exploded as the Queen of Soul: “Then there’s the Royal Peacock,. Let me tell you that was as hot it could get.”