3 MEMORIES OF MELVIN VAN PEEBLES

The versatile writer, filmmaker and musician died September 21, 2021

MEETING MELVIN 1978

When I was attending St. John’s University in New York in the late ‘70s, I didn’t wait for graduation to start my career. I had an internship at both Billboard, the music trade publication, and the black weekly Amsterdam News, where I was able to cover sports and write movie reviews. Being a studious nerd, I read every book on black film I could find – not that there were many – and obsessed over Donald Bogle’s ‘Bucks, Toms, Coons & Mulattos’ and Thomas Cripps’ ‘Black Film As Genre.’ I took classes in college on the history of jazz, the history of foreign film, and movie reviewing. I haunted New York’s many revival houses, seeing the old Hollywood all-black musicals ‘Green Pastures’ and ‘Cabin in the Sky.’ Through museum screenings organized by historian Pearl Bowser, I saw the work of black film pioneer Oscar Micheaux. Through the then new Black Filmmaker Foundation, organized by filmmaker Warrington Hudlin, I witnessed the early work of Julie Dash, Charles Burnett, and his younger brother Reggie.

But the one film that really rocked by world was Melvin Van Peebles’ ‘Sweet Sweet Back’s Badass Song.’ As an adolescent I’d watched most of the blaxploitation era hits (‘Shaft,’ ‘Super Fly,’ ‘Foxy Brown’) in Times Square. But my mother, who was very liberal in taking me to see edgy movies, wouldn’t take me to see the X rated ‘Sweetback,’ so I didn’t see the film until I was at St. John’s. Leaving the cinema, I knew Van Peebles’ was a man I wanted to meet.

Routes was a short-lived 1970s black lifestyle mag that I was able to use my Amsterdam News clips to get some assignments from. Somehow,= I convinced them to let me interview the multi-hyphenate director, writer, and singer-songwriter. At that time, I was just hip to his landmark film and his two Broadway plays (‘Ain’t Supposed to Die a Natural Death,’ ‘Don’t Play Us Cheap’). That he’d recorded several albums and had started his film career in France were just a few of the details I was ignorant of but, as I’d discover, there was a lot to know about Melvin.

I found a number for his Yeah, Inc. and cold called. I’m not sure if I spoke to him or an assistant, but I got an appointment. Melvin’s office was on Seventh Avenue in the West 50s, an area full of little walk-up stone pre-War buildings filled with managers, talents, publicists and production companies - spaces I’d spent a lot of my years as a music journalist going in and out of.

I was just past wearing a suit & tie to conducting interviews, but I was looking low rent preppy when I walked up the steps to Melvin’s office. I’d been raised on Sidney Poitier movies and, at that point, had some very conventional ideas on what black success looked like. So, when I entered the man’s office, I was expecting Melvin to be wearing a shirt, tie and maybe a suit.

Instead Melvin sat in a rocking chair, wearing a brown fedora, suspenders, trousers and was smoking a cigar minus shoes and shirt. This man wasn’t reading from the civil rights textbook of upwardly mobility I’d been raised on. Melvin was, as the Sweet Back film suggested, writing his own book. This was my first encounter with a real black iconoclast, someone who had a unique, funny, uncompromising point of view.Melvin told me, “Sweetback is an outsider in the truth sense. They took that hero and made those heroes work, to some degree, within the framework of the establishment by means of badge or the revenge motive. They were driven by some majority mainstream motivation.” When I asked Melvin if he was going to mount a sequel to ‘Sweetback’ and, if somewhat would be about, he gave me a classic Van Peebles answer: “The script exist, but it’s been on ice since 1971… It’s the same old shit – only better. I am just a nigger who got tired of looking at shit. So I made what I wanted to see. Turns out everybody else wanted to see what I wanted to see.”

Individualistic, political and very much himself, Melvin wasn’t like anyone I’d met before and no one I would meet after. He was profoundly himself. At 21, I wanted to me myself too – once I’d figured out who I was.

HELPING MELVIN 1995

In 1995 I was able to do Melvin a solid. After not having a record deal since 1974, Melvin was signed by Capitol for a new album called ‘Ghetto Gothic.’ Like the Last Poets and Gil Scott-Heron, Melvin’s ‘70s albums were now being viewed as a precursor to rap music. He called me to write liner notes on the album which, at the time which were, except for re-issues, increasingly rare. Frankie Crocker, WBLS radio station’s program director, drive time DJ, and Big Apple music kingmaker, embraced the song, “The Apple Stretching,” giving it a little life in the city. A few years later that song would be covered by Grace Jones and would become a minor dance club favorite.

Melvin, like many original thinkers, had his own language, a mixture of old Negro slang, self-aware hogwash, international lingo, and searing social commentary. Whether it was in one of his plays or in person while he puffed on a cigar, Melvin used language as playground for his idiosyncratic vision. He was a very serious man, but that never got in the way of an antic wit as singular as his vast body of work. In fact, his humor was a reflection of his seriousness in that he consistently torn holes in conventional thinking with a torrent of wit.

Whenever I was in Melvin’s presence, I felt like I was always trying to keep up, because there was a lesson in there but, if you missed the set-up, the message would elude you. He was deeply connected to modes of storytelling that went back to the 19th and early 20th century, the blues, and Mark Twain’s tall tales, so I needed to focus to catch the meanings behind the story. In the ‘90s opportunities to work in film opened up for young black filmmakers in the wake of Spike Lee’s ‘She’s Gotta Have It’ and I began working as a screenwriter and producer, feeling this period of black cinematic expansion was an echo of Melvin’s impact with Sweet Back.

MELVIN HELPING ME 2011

As much as Melvin was a cinematic inspiration, he also opened up Europe to me. In the late ‘90s I was in Paris and attended a symposium at the Sorbonne on the role of African-American writers in Paris. While there I got in contact with Melvin and had a magical dinner with him, ex-Black Panther Kathleen Cleaver, Professor Henry Louis Gates, and a black French academic who’s name I’ve forgotten. We ate at a Left Bank bistro and then strolled down Boulevard Saint Germain, where Melvin related stories of Gordon Parks, shooting his first film, ‘The Story of a Three Day Pass,’ and wooing French women.

In my forties and fifties, I put an emphasis on being more of a global citizen, traveling to South America, Eastern Europe, and Africa, expanding my understanding of the world and the black presence in it – expansion of my consciousness Melvin deeply influenced. Out all that travel came a project I called Migrations, a mix of interviews and fictional scenes about global black identity I shot in Berlin, Amsterdam, London, Toronto, Paris as well as in New York and Los Angeles. The lead in this project was an Ethiopian/German actress, Tigist Selam, who was smart, bilingual, but not very experienced.

I got a bold idea – if I was gonna attempt a film about global black identity, I couldn’t do this without Melvin. So one afternoon Tigist and I went up to Melvin’s apartment on West 57th Street to do an semi-improvised scene. Melvin’s living room was filled with whimsical paintings and odd objects he’d designed, like the rear of a Volkswagen van that spewed smoke and a chest carved in the image of a giant hot dog and bun – all of its testament to his vivid imagination.

The shooting went awkwardly at first. Admittedly the script was not my greatest best work and Tigist seemed, rightly, intimidated acting opposite a legend. Then Melvin took control, going off the script and gently helping Tigist (and me) give the scene shape by giving her verbal cues that pushed the story forward. For a man who’d been making progressive art for decades, it was a master class in how to turn shit to gold. I never pulled the whole project together – I just made a few short films with the material – but I have vowed to one day cut the footage with Tigist and Melvin into a short piece, since it’s a prime example of Melvin’s inventiveness, humor, and generosity.

ETERNAL MELVIN 2023

I’d always known Melvin to be a ladies’ man. The testimony at the memorial service was punctuated by various women expressing their devotion to him. At the time of his death, apparently, several of his lovers were active in looking after him. What I didn’t know until after his death is that Melvin had indulged in the era’s progressive ‘70s sex scene. He’d an active “swinger,” throughout his life and a regular at Plato’s Retreat in Manhattan, which had been the epicenter of the couples swapping partners in the ‘70s and ‘80s. In the documentary, ‘American Swing,’ Melvin is interviewed in his apartment about the sex club, saying with a smile: “Say you got a date. You want a night out etc etc. You got a date that’s sort of on the wild side – boom! Personally, with a little encouragement, everybody’s got a wild side.” He’d burst into cinematic history in ‘Sweetback’ playing a sex worker with a taste for rebellion, and his passion for sexual expression did not abate with time. He began a relationship the saxophonist Paula Henderson, who’d played in his band Laxative, when he she was in her 40s and he was 77.

You rarely saw the top of Melvin’s head in person in public, since it was always topped with a fedora, a news boys cap, or a scarf. Even when he was shirtless, Melvin would rock suspenders and trousers. So Melvin was always immaculately layered in garb that spoke to his carefully cultivated sense of self. Not surprising for an artist practiced so many disciplines, Melvin’s look was as curated as the many large, odd self-designed art pieces that decorated his Manhattan apartment.

I didn’t really become a devotee of smoking cigars until after Melvin’s death, but I believe his lifelong habit made them seem attractive to me. When I adopted it as a calming pandemic era pastime, I often regretted I never got to share the brotherhood of tobacco with him. So when I when light up I often think of him and treasure the time I’d spent with him and his mentorship.

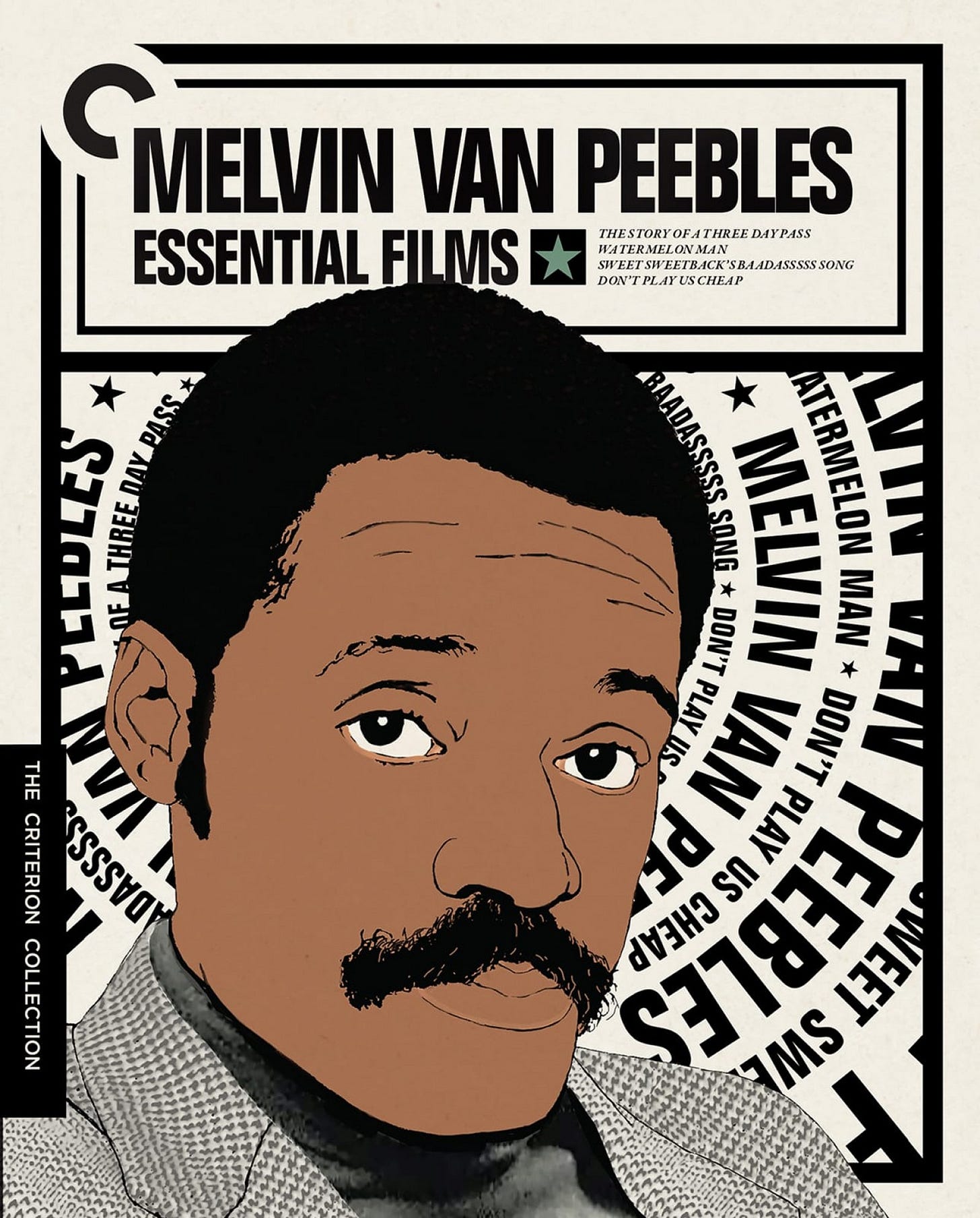

https://www.criterion.com/boxsets/4787-melvin-van-peebles-essential-films

To get a sense of the spread of his filmmaking, his humor and social commentary, please use this link to the Criterion Collection, which released a boxed set of his four of his fims, just a few years ago.

Thanks, Nelson. He was a wonder and a treasure (and so are you).